For something I’m working on: we know that China is pursuing a mercantilist policy: keeping the renminbi weak through a combination of capital controls and intervention, leading to trade surpluses and capital exports in a country that might well be a natural capital importer. We also know, or should know, that this amounts to a beggar-thy-neighbor policy — or, more accurately, a beggar-everyone but yourself policy — when the world’s major economies are in a liquidity trap.But how big is the impact? Here’s a quick back-of-the-envelope assessment.

Start with the Chinese surplus. It has been temporarily depressed by the world trade collapse, but seems to be on the rise again. Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti, at the IMF but speaking for themselves, project a Chinese current account surplus for 2010-2014 of 0.9 percent of gross world product.

You can think of this as a negative shock to rest-of-world net exports. (Technically, that’s not quite correct — because the shock depresses res-of-world GDP and hence rest-of-world imports from China, the realized trade surplus is smaller than the shock. But that’s a small correction.)

In turn, this negative shock is like a negative shock to government purchases of goods and services. So it should have a similar multiplier. Multiplier estimates are all over the place, but tend to cluster around 1.5. So we’re looking at a negative impact on gross world product of around 1.4 percent. Not huge — China isn’t the principal obstacle to recovery — but significant.

And, if we think of the United States as bearing a proportionate share, and also use the rule of thumb that one point of GDP = 1 million jobs, we’re looking at 1.4 million U.S. jobs lost due to Chinese mercantilism.

Search This Blog

Thursday, December 31, 2009

Economics and Politics - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Sunday, December 20, 2009

What is it with Microeconomists?

What is it with Microeconomists?

They are certainly not stupid. And they are certainly not ignorant either. I know that the ones I'm complaining about are smarter than me, and more knowledgeable than me. And that includes economics smarts and knowledge. Some of them make me feel totally inadequate on a daily basis (I read their blogs daily). Some of my best friends are microeconomists. But they just don't get macro!

I'm talking about money wages and employment. I can't be bothered to link to the posts I'm complaining about. And I can't be bothered to go through those posts and explain why their reasoning is wrong. Others have done this, and have failed. Or at least, have failed to make any impression on the 'microeconomic miscreants'. They seem to be preaching to the choir; and the choir is composed of macroeconomists.

I want to try a different tack. I'm not going to try to show that they are wrong. I want to try to understand why they keep going wrong.

But I'm not altogether sure why they keep going wrong. I have three theories, and am going to run through each in turn. Actually, I think we probably need all three theories to explain why microeconomists are just so confused about macro. ...

If all apples were identical, there would be no need for trade. Each worker would eat his own apples. No worker could be unemployed; he could just grow as many apples as he wanted to eat, and eat his own apples.

Even if apples came in different varieties, or there were a tabu against workers eating their own apples, if barter were easy there could never be unemployment. The unemployed workers could all just get together and swap all the apples they wanted to produce and sell. In barter, a supply of apples is a demand for apples.

It is monetary exchange (or rather, the high transactions costs of barter that make monetary exchange essential) that is the root of all deficiencies in aggregate demand. Each worker's apples are sold in his own private market. And they are sold for money, the medium of exchange. To demand apples is to supply money in exchange. And if people want to hang onto their money, rather than buy apples with it, the demand for apples, and the demand for labour, will be deficient.

A deficiency of aggregate demand has got nothing whatsoever to do with a deficiency of income. Income is always sufficient. It's always the same as goods sold. A deficiency of aggregate demand is a deficiency of peoples' willingness to get rid of money. The 'Paradox of Thrift', and the 'Paradox of Toil', are merely corrupt versions of, or way-stations to, the Paradox of Money. Each individual can increase his stock of money by buying less; but in aggregate they fail, but cause unemployment as a side-effect."

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

FT.com / Comment / Opinion - Bankers had cashed in before the music stopped

It is true that the top executives at both banks suffered significant losses on shares they held when their companies collapsed. But our analysis, using data from Securities and Exchange Commission filings, shows the banks’ top five executives had cashed out such large amounts since the beginning of this decade that, even after the losses, their net pay-offs during this period were substantially positive.

In 2000-07, the top five executives at Bear and Lehman pocketed cash bonuses exceeding $300m and $150m respectively (adjusted to 2009 dollars). Although the financial results on which bonus payments were based were sharply reversed in 2008, pay arrangements allowed executives to keep past bonuses.

Furthermore, executives regularly took large amounts of money off the table by unloading shares and options. Overall, in 2000-08 the top-five teams at Bear and Lehman cashed out close to $2bn in this way"

Monday, December 7, 2009

Unhelpful Hansen - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Unfortunately, while I defer to him on all matters climate, today’s op-ed article suggests that he really hasn’t made any effort to understand the economics of emissions control. And that’s not a small matter, because he’s now engaged in a misguided crusade against cap and trade, which is — let’s face it — the only form of action against greenhouse gas emissions we have any chance of taking before catastrophe becomes inevitable.

What the basic economic analysis says is that an emissions tax of the form Hansen wants and a system of tradable emission permits, aka cap and trade, are essentially equivalent in their effects. The picture looks like this:

A tax puts a price on emissions, leading to less pollution. Cap and trade puts a quantitative limit on emissions, but from the point of view of any individual, emitting requires that you buy more permits (or forgo the sale of permits, if you have an excess), so the incentives are the same as if you faced a tax. Contrary to what Hansen seems to believe, the incentives for individual action to reduce emissions are the same under the two systems.

This is true even if some emitters are “grandfathered” with free allocations of permits, as will surely be the case. They still have an incentive to cut their emissions, so that they can sell their excess permits to others.

The only difference is the nature of uncertainty over the aggregate outcome. If you use a tax, you know what the price of emissions will be, but you don’t know the quantity of emissions; if you use a cap, you know the quantity but not the price. Yes, this means that if some people do more than expected to reduce emissions, they’ll just free up permits for others — which worries Hansen. But it also means that if some people do less to reduce emissions than expected, someone else will have to make up the shortfall. It’s symmetric; there’s no reason to emphasize only one side of the story.

And as far as I can see, the question about uncertainty is secondary; the fact is that cap and trade works. Hansen admits that the sulfur dioxide cap has reduced pollution, but argues that it didn’t do enough; well, it did as much as it was designed to do. If Hansen thinks it should have done more, he should be campaigning for a lower cap, not trashing the whole program.

Oh, and the argument that if you create a market, you’re opening the door for Wall Street evildoers, is bizarre. Emissions permits aren’t subprime mortgages, let alone complex derivatives based on subprime; they’re straightforward rights to do a specific thing. It will truly be a tragedy if people generalize from the financial crisis to block crucially needed environmental policy.

Things like this often happen when economists deal with physical scientists; the hard-science guys tend to assume that we’re witch doctors with nothing to tell them, so they can’t be bothered to listen at all to what the economists have to say, and the result is that they end up reinventing old errors in the belief that they’re deep insights. Most of the time not much harm is done. But this time is different.

For here’s the way it is: we have a real chance of getting a serious cap and trade program in place within a year or two. We have no chance of getting a carbon tax for the foreseeable future. It’s just destructive to denounce the program we can actually get — a program that won’t be perfect, won’t be enough, but can be made increasingly effective over time — in favor of something that can’t possibly happen in time to avoid disaster.

"Matthew Yglesias » Manmohan Singh

Sunday, December 6, 2009

The Wrong Jobs Summit - J. Bradford DeLong's Grasping Reality with All Eight Tentacles

Irving Fisher first analyzed the market for liquidity—the money market—which matches the supply of readily spendable purchasing power in the economy (cash, checking account balances, credit lines) with the demand of households and businesses to hold some of their wealth in the form of readily spendable purchasing power. Supply and demand in this market is influenced by interest rates and the flow of spending.

Knut Wicksell first analyzed the market for savings—usually called “the bond market”—which matches households wishing to boost the value of their savings with businesses seeking capital to expand their productive capacity. Interest rates are crucial here, as well.

At first glance, it seems there are three variables at play: spending, income, and interest rates. But when we recognize that everyone’s spending is someone else’s income, we see that there are really only two variables—that the economy will settle at that level of interest rates, spending, and income where supply equals demand in the market for liquidity and in the market for savings.

We now have a framework for managing the economy. For the government to boost jobs, it must to do something to change the balance of supply and demand in either the market for liquidity or the market for savings. In general, the central bank—the Federal Reserve—acts to tweak supply and demand in the market for liquidity. The president and Congress act to tweak supply and demand in the market for savings. But they must make sure that whatever spending, income, and job-stimulating effect they create by intervening in one market is not undone by changes in the other market.

Right now, if you ask the decisive members of congress—by which I mean the Blue Dog Democrats in the House, or the most conservative Democrats and most liberal Republicans in the Senate —why the president and the Congress are not doing more to reduce unemployment and boost spending and income, the answer you’ll get is ... well, you probably wouldn't get an intelligible answer.

But if you did get an explanation for the lack of congressional action it would go something like this: Attempts to move supply and demand in the market for savings in order to boost spending would (a) increase the national debt burden on future taxpayers and (b) lead to a large decline in bond prices and a boost in interest rates. Why? Because businesses would try to increase their liquidity to support higher spending, driving up interest rates, which, in turn, would cause businesses to cut back on investment, thus neutralizing most or all of the stimulative policies.

Similarly, if you were to ask the Federal Reserve why it isn’t doing more to reduce unemployment and boost spending and income, the answer you would get is this: Spending is in no way constrained by a shortage of liquidity. We have already done all we can do, indeed we have “flooded the zone” with liquidity. As a result, the Fed is disinclined to pursue additional tweaks of supply and demand in the market for liquidity because it fears such efforts would fuel destructive inflation in the future without boosting employment and spending in the present.

Both of these arguments are comprehensible; each might well be true. But they cannot both be true at the same time. Either the economy is so awash in liquidity that the Federal Reserve cannot do much to boost spending—in which case additional spending by the government won’t generate any substantial rise in interest rates. Or additional government spending will crowd out investment as businesses scramble for liquidity and interest rates rise—in which case the economy is not awash in liquidity, and quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve could do a lot right now to boost spending and employment.

It appears that what we have here is a failure to communicate.

In truth, that is nothing new on this front. It was clear, for example, by Feb. 17 of this year, the day Obama signed the stimulus package, that the economy was in much worse shape than earlier projections had supposed. The administration’s policies were targeted at an economy in which the current—December 2009—unemployment rate was projected at 7.8 percent, with a decline to 6.9 percent projected by December 2010.

But we do not live in that world. We live in a world in which the unemployment rate this month is likely, in the final data, to come in at 10.4 percent, and in which the unemployment rate in December 2010 may well exceed 9.6 percent."

Friday, November 27, 2009

Deficits: the causes matter - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Broadly speaking, there are two ways you can get into severe deficits: fundamental irresponsibility, or temporary emergencies. There’s a world of difference between the two.Consider first the classic temporary emergency — a big war. It’s normal and natural to respond to such an emergency by issuing a lot of debt, then gradually reducing that debt after the emergency is over. And the operative word is “gradually”: it would have been incredibly difficult for the United States to pay off its World War II debt in ten years, which Jim apparently thinks is the right way to view debts incurred more recently; but it was no big deal to stabilize the nominal debt, which is roughly what happened, and as a result gradually reduce debt as a percentage of GDP.

Consider, on the other hand, a government that is running big deficits even though there isn’t an emergency. That’s much more worrisome, because you have to wonder what will change to stop the soaring debt. In such a situation, markets are much more likely to conclude that any given debt is so large that it creates a serious risk of default.

Now, back in 2003 I got very alarmed about the US deficit — wrongly, it turned out — not so much because of its size as because of its origin. We had an administration that was behaving in a deeply irresponsible way. Not only was it cutting taxes in the face of a war, which had never happened before, plus starting up a huge unfunded drug benefit, but it was also clearly following a starve-the-beast budget strategy: tax cuts to reduce the revenue base and force later spending cuts to be determined. In effect, it was a strategy designed to produce a fiscal crisis, so as to provide a reason to dismantle the welfare state. And so I thought the crisis would come.

In fact, it never did. Bond markets figured that America was still America, and that responsibility would eventually return; it’s still not clear whether they were right, but the housing boom also led to a revenue boom, whittling down those Bush deficits.

Compare and contrast the current situation.

Most though not all of our current budget deficit can be viewed as the result of a temporary emergency. Revenue has plunged in the face of the crisis, while there has been an increase in spending largely due to stimulus and bailouts. None of this can be seen as a case of irresponsible policy, nor as a permanent change in policy. It’s more like the financial equivalent of a war — which is why the WWII example is relevant.

So the debt question is what happens when things return to normal: will we be at a level of indebtedness that can’t be handled once the crisis is past?

And the answer is that it depends on the politics. If we have a reasonably responsible government a decade from now, and the bond market believes that we have such a government, the debt burden will be well within the range that can be managed with only modest sacrifice.

OK, that’s a big if. But it’s not a matter of dollars and cents; it’s about whether America is still America.

Sunday, November 22, 2009

The Subprime Student Loan Racket - Stephen Burd

As a result of these changes, private loan borrowing has skyrocketed. In the last decade alone, it has grown an astounding 674 percent at colleges overall, when adjusted for inflation. The growth has been most dramatic at for-profit colleges, where the percentage of students taking out private loans jumped from 16 percent to 43 percent between 2004 and 2008, according to Department of Education data.

The spike in private loan borrowing is dismal news for students. Unlike traditional student loans, which have low, fixed interest rates, private educational loans generally have uncapped variable rates that can climb as high as 20 percent—on par with the most predatory credit cards. Private loans also come with much less flexible repayment options. Borrowers can’t defer payments if they suffer economic hardship, for instance, and the size of their payment is not tied to income, as it sometimes is in the federal program. Private loans also lack basic consumer protections available to federal loan borrowers. With a traditional federal student loan, for example, if a borrower dies or becomes permanently disabled, the debt is forgiven, meaning they or their kin are no longer responsible for paying it off. The same goes if the school unexpectedly shuts down before a student graduates. But none of this is true of private loans. Also, because it is so difficult to discharge private student loans in bankruptcy, when students take them out to attend schools that provide no meaningful training or skills they can find themselves trapped in a spiral of debt that they have little prospect of escaping."

Friday, November 20, 2009

Matthew Yglesias » The Three Percent Solution

DeLong comments:

Matthew Yglesias » The Three Percent Solution:I do wonder how much good would be done if the FOMC were simply to stand up and announce that they were raising their long-term GDP-deflator inflation target from 2% to 3%. It might do a lot of good. And it is certainly something the Fed could do without cracking its credibility as committed to low inflation.

But they won’t. We would need a very different FOMC than the one we have to consider such a move.

the Fed could stimulate the economy by raising its long-term inflation target from two percent to three percent it’s worth noting that there are other arguments for thinking that this would be a good idea. First off, it’s worth noting that three percent inflation is still pretty low. There’s nothing magical about the two percent number, and a somewhat higher figure is still very much consistent with the basic idea that low inflation is good.

Second, a higher inflation rate would speed the process by which households climb out from over-indebtedness. Third, a higher inflation rate would ensure that in the future the Fed has more “running room” for conventional monetary policy before hitting the zero bound and getting into this madness. Fourth, a higher inflation rate would speed the process by which real wages and prices adjust to whatever real shocks the economy may or may not be suffering from.

This course of action seems to be anathema to the powers that be, but it seems strongly preferable to a prolonged period of ten percent unemployment and a possible series of trade wars and the like.

Monday, November 16, 2009

How the tax code encourages debt : The New Yorker

How the tax code encourages debt : The New Yorker: "The government doesn’t make people go into debt, of course. It just nudges them in that direction. Individuals are able to write off all their mortgage interest, up to a million dollars, and companies can write off all the interest on their debt, but not things like dividend payments. This gives the system what economists call a “debt bias.” It encourages people to make smaller down payments and to borrow more money than they otherwise would, and to tie up more of their wealth in housing than in other investments. Likewise, the system skews the decisions that companies make about how to fund themselves. Companies can raise money by reinvesting profits, raising equity (selling shares), or borrowing. But only when they borrow do they get the benefit of a “tax shield.” Jason Furman, of the National Economic Council, has estimated that tax breaks make corporate debt as much as forty-two per cent cheaper than corporate equity. So it’s not surprising that many companies prefer to pile on the leverage.

There are a couple of peculiar things about these tax breaks—which have been around as long as the federal income tax. The first is that they’re unnecessary. Few people, after all, can save enough to buy a home with cash, so home buyers naturally gravitate toward mortgages. And businesses like debt because it offers them tremendous leverage, making it possible to put down a little money and potentially reap a huge gain. Even in the absence of the deductions, then, there would be plenty of borrowing. The second thing about these breaks is that their social benefits are pretty much nonexistent. Advocates of the mortgage-interest deduction, for instance, claim that it increases homeownership rates. But it doesn’t: in countries where mortgage deductions have been eliminated, homeownership rates haven’t dropped. Instead, the deduction simply inflates house prices. The business-interest deduction, meanwhile, may lower an individual company’s taxes, but it also means that the over-all corporate tax rate is higher, so its real impact is to give companies with lots of debt an unjustified advantage.

If the benefits are illusory, the costs are all too real. Economies work best, generally speaking, when people are making decisions based on economic fundamentals, not on tax considerations. So, as much as possible, the tax system should be neutral between debt and equity, and between housing and other investments. It’s not, and, worse still, as we’ve seen in the past couple of years, debt magnifies risk"

Saturday, November 14, 2009

The Debit Card Hustle | Mother Jones

Hogwash. It's a small, short-term loan, just like a credit card charge. The APR should be somewhere in the neighborhood of 10-30%, like a credit card, with perhaps a small processing fee added to that. And since we live in an electronic era, that processing fee is small: maybe 50 cents or so. A dollar max.

But the Fed did nothing about that. Or about the number of fees banks can charge per day. Or about re-ordering of fees to run up total charges."

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Worthwhile Canadian Initiative: Why do central banks have assets?

If you look at the balance sheet of a central bank, you will see it has liabilities (mostly currency) and assets (normally mostly government bonds/bills). Why do central banks have assets? Do they need them?

The wrong answer is that central banks need assets to 'back' the value of the currency, and that paper currency would be worthless otherwise. The right answer is: since the government gets all the profits from a central bank anyway, there's no point in giving the government the assets; that owning assets lets the bank reverse course and reduce the money supply if it ever needs to; and it stops the accountants freaking out.

Let's deal with the wrong answer first. According to the 'backing' theory of the value of money, the value of a central bank's currency is equal to and determined by the value of the central bank's assets backing the currency. (This is different from the fiscal theory of the price level, which says that the value of currency plus bonds is equal to and determined by the present value of primary fiscal surpluses.)

The backing theory sounds good. How can intrinsically worthless paper money have value? Because it is backed by valuable assets. It's just like shares in a mutual fund, which have value equal to and determined by the value of the assets in the fund.

Here are three arguments against the backing theory of money:

1. The assets of central banks are normally nearly all nominal assets, denominated in the same currency as the liabilities. Suppose the price level were to double magically overnight, and the real value of currency halved. The real value of the bonds held by the central bank would also halve. So a magical doubling of the price level would not violate the equality between the value of the currency and the value of the assets backing it. The backing theory leaves the price level indeterminate. It could only pin down the price level if the assets were real assets. If (say) 10% of the bank's assets were real (gold reserves, plus the building), then a 1% loss of its real assets (the building burns down) would cause a 10% jump in the price level.

2. Suppose a mutual fund held bonds, but all the interest on the bonds (minus the administrative expenses of running the fund) were handed over to some third party, and not to the owners of shares in the mutual fund. Who would want to own shares in that mutual fund? The net present value of the dividends paid to the shareholders would be zero, so the shares would be worth zero too. But this is exactly what central banks do. Every year central banks earn profits from the interest on the bonds they own, minus administrative expenses, and hand the whole of that profit to the government, not to the holders of currency.

3. We don't need 'backing' to explain why money has value. People want to hold a stock of money because money is a medium of exchange, and holding a stock of the medium of exchange makes shopping easier. This creates a (stock) demand for money. Provided the central bank restricts the supply of money, the intersection of demand and supply curves creates a positive equilibrium value of money (a finite price level). Now you could argue that if paper money were worthless it could not function as a medium of exchange, so you need to assume paper money has value in order to explain the value it has, so the demand and supply theory of the value of money begs the question.

There is some truth in this criticism of standard theories of the value of money. There are indeed two equilibria: the normal one, where paper money has value, and a weird one, where it is worthless. But Ludwig von Mises, for example, addressed this problem in 1912 with his Regression Theory of Money. Historically, money needed to be commodity money, or have commodity backing, in order to get started. But once it does get started, as a social institution, the demand for a medium of exchange supplements the industrial demand for the commodity, and the commodity backing can eventually be withdrawn as custom keeps us out of the weird equilibrium. (When Cambodia reintroduced paper money, after the fall of the Kymer Rouge, it could not create paper money ex nihilo, but initially made it convertible into rice, IIRC.)

A Ponzi scheme is a financial institution with liabilities and no assets backing those liabilities. Paper money can operate just like a Ponzi scheme, but with one important difference. Mr Ponzi promised his clients high rates of interest and/or capital gains. They would not have held his liabilities unless they believed him. The Bank of Canada promises zero interest, zero nominal capital gains, and a minus 2% real rate of interest on people who hold its paper money. Mr Ponzi could not deliver on his promise, even if he hadn't spent the assets. The Bank of Canada can deliver on its promise, even if it gave away all its assets, provided the (real) demand for its paper money does not fall over time more quickly than 2% per year. (If the real demand for money were falling at 2% per year, a constant nominal supply of money would yield 2% annual inflation).

The Bank of Canada does not need assets, because the long run growth in the (real) demand for its paper exceeds the real interest rate at which people are willing to hold its paper. If Mr Ponzi could have met the same test, he wouldn't have needed assets either. People are willing to hold paper money, even at very negative real rates of return (Zimbabwe), because doing so makes shopping easier."

Friday, November 6, 2009

Matthew Yglesias » Politics and Public Works

Unemployment Rises Above 10 Percent for the First Time in 26 Years

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

The story so far, in one picture - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

CRE and the CRA

One of the enduring myths of the financial crisis has been the claim that it was the result of (a) Fannie and Freddie (b) the Community Reinvestment Act, which forced poor, helpless bankers to make loans to you-know-who. It’s a myth that won’t go away...But commercial real estate had the same kind of bubble without any government help.

there was no federal act driving banks to lend money for office parks and shopping malls; Fannie and Freddie weren’t in the CRE loan business; yet 55 percent — 55 percent! — of commercial mortgages that will come due before 2014 are underwater. The lenders didn’t need government urging to dive deep into a property bubble, and drown.

Crisis Compels Economists To Reach for New Paradigm - WSJ.com

The play's focus is collateral, with the money lender Shylock demanding a particularly onerous form of recompense if his loan wasn't repaid: a pound of flesh. Mr. Geanakoplos, too, finds danger lurking in the assets that back loans. For him, the risk is that investors who can borrow too freely against those assets drive their prices far too high, setting up a bust that reverberates through the economy."

EconomPic: Problem Banks on a Parabolic Rise

The Problem Bank List is the FDIC’s internal list of financial institutions that the FDIC believes are in danger of failure."

And the chart...

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Growth and jobs: the lesson of the Clinton years

Just a quick further note on my growth and jobs post. To get a sense of what 3.5% growth does and doesn’t mean, we can look at the Clinton years, viewed as a whole. (I’m using end-1992 to end-2000, but it doesn’t really matter if you vary the start and end dates a bit).

Over that 8-year stretch, real GDP grew at an average annual rate of 3.7%. (Did you know that? My sense is that very few people realize just how good the Clinton-era growth record was). Over the same period, the unemployment rate fell from 7.4% to 3.9%, a 3.5 percentage point decline.

So if we take 3rd quarter growth to be more or less equivalent to average Clinton-era growth, even after 8 years of growth at that rate we’d only expect unemployment to have fallen from the current 9.8% to a still uncomfortably high 6.3%. It would take us around a decade to reach more or less full employment. As I said in my previous post, that’s well into President Palin’s second term.The implications for Fed policy are also striking. If we use a Taylor rule that suggests zero rates until the unemployment rate reaches the vicinity of 7%, the Fed should stay on hold for around 6 more years.

We need much faster growth.

Long-Term Unemployment

Economist's View

[Calculated as the this divided by the this.]

Thursday, October 29, 2009

EconomPic: Thank You Cash for Clunkers

Motor vehicles added a whopping 1.66% of the 3.5% growth in Q3 GDP. More specifically, motor vehicle output was up... wait for it... 157.6% on an annualized basis.

Growth and jobs

Just a quick note on the GDP report. Obviously, 3.5 percent growth is a lot better than shrinkage. But it’s not enough — not remotely enough — to make any real headway against the unemployment problem. Here’s the scatterplot of annual growth versus annual changes in the unemployment rate over the past 60 years:Basically, we’d be lucky if growth at this rate brought unemployment down by half a percentage point per year. At this rate, we wouldn’t reach anything that feels like full employment until well into the second Palin administration.BEA, BLS

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

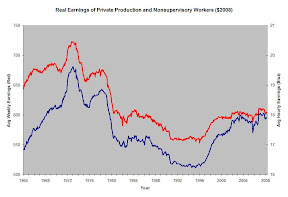

Real Earnings, Not So Much

The discrepancy between the series is the change in hours over this period--the series for average weekly earnings falls over the period because hours fall more than enough to offset the slight rise in average hourly earnings. Over this period, private employment has been a fairly constant share of total nonfarm employment (a bit more than 80%) and production and non-supervsory employment has been a fairly constant share of total private employment (

This is one of the most depressing graphs I've ever seen.

LABOR'S SHARE

This shift to an environment of stronger productivity and weaker real growth generated an interesting development that has received little attention among economists or in the business press.

This development was a secular decline in labor's share of the pie. Prior to the 1982 recession there was a strong cyclical pattern of labor's but it was around a long term or secular flat trend. But since the early 1980s labor's share of the pie has fallen sharply by about ten percentage points. Note that the chart is of labor compensation divided by nominal output indexed to 1992 = 100. That is because the data for each series is reported as an index number at 1992=100 rather than in dollar terms. So the scale is set to 1992 =100 rather than in percentage points. But it still shows that labor payments as a share of nonfarm business total ouput has declined sharply over the last 20 years and prior to the latest cycle we did not even see the normal late cycle uptick in labor's share.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Adjustment and the dollar

...imagine what the world might look like if it (1) returns to more or less full employment (2) experiences a significant reduction in imbalances — in particular, a much lower US trade deficit.

For (2) to happen, the US must start spending more within its means; overall spending will have to fall relative to GDP. Correspondingly, spending in the rest of the world must rise.

But that’s not the end of the story. Suppose that spending in the United States falls by $500 billion, while spending in the rest of the world rises by $500 billion. Other things equal, most of that decline in US spending would fall on US-produced goods and services. Remember, even if you buy Chinese stuff at Walmart, much of the price represents US distribution and retailing costs. The world, you might say, is a long way from being truly flat.Meanwhile, a much smaller fraction of the rise in spending abroad will fall on US products. So other things equal, this reallocation of spending would lead to an excess supply of US goods and services, an excess demand for goods and services produced elsewhere. (Trade economists know that I’m talking about the transfer problem.)

So something has to give — specifically, the relative price of US output, and along with it such things as US relative wages, has to fall.

There are three ways this could happen: (1) deflation in the United States (2) inflation in the rest of the world (3) a depreciation of the dollar against other currencies. Leave (2) aside, on the grounds that central banks will fight it. Then the choice is between (1) and (3).

And here’s the thing: deflation is hard (ask Spain), because prices are sticky in nominal terms. How do we know that? Lots of evidence. See, for example, A Sticky Price Manifesto by Larry Ball and some guy named Mankiw. But the most compelling evidence — familiar to international macro people, but oddly uncited by most domestic macroeconomists — comes from exchange rates.

The first person to make this point was probably none other than Milton Friedman (cue Brad DeLong on the decline of the Chicago School), but the really influential quantitative analysis was by Michael Mussa.

Mussa pointed out that a funny thing happens when countries move from fixed to floating exchange rates: the nominal exchange rate becomes much more variable, of course, but so does the real exchange rate — the exchange rate adjusted for price levels. Meanwhile, relative inflation rates remain within a narrow band. The obvious interpretation is that once the exchange rate is freed, it bounces around a lot, while domestic prices in domestic currency are sticky, and don’t move much.

Here’s an updated version of Mussa’s point. The top figure shows quarterly log changes in the US-Germany real exchange rate; the bottom figure divides this into nominal exchange rate changes and inflation differentials. The Mussa point is crystal clear.

So, the bottom line: to narrow international imbalances, we need a lower relative price of US output. Because prices are sticky, by far the easiest way to get there is dollar depreciation.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Matthew Yglesias » Another Spin at the Wheel

The way this works is that you identify arbitrage opportunities such that you make trades you’re overwhelmingly likely to make money on. But those opportunities only exist because the opportunities are very small. So to make them worth pursuing, you need to lever-up with huge amounts of debt. Which means that on the rare moments when the trades do go bad, everything falls apart: “The strategy typically has a high ‘blow-up’ risk because of the large amounts of leverage it uses to profit from often tiny pricing anomalies.”

As a friend puts it, this strategy is “literally the equivalent of putting a chip on 35 of the 36 roulette numbers and hoping for no zero/36.” But you’re doing it with borrowed money. I’m not a huge believer in human rationality, so I totally understand how this scam worked once. That he was able to get a second fund off the ground is pretty amazing."

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Thinking about the liquidity trap

Krugman 1999:

We live in the Age of the Central Banker - an era in which Greenspan, Duisenberg, and Hayami are household words, in which monetary policy is generally believed to be so effective that it cannot safely be left in the hands of politicians who might use it to their advantage. Through much of the world, quasi-independent central banks are now entrusted with the job of steering economies between the rocks of inflation and the whirlpool of deflation. Their judgement is often questioned, but their power is not.

It is therefore ironic as well as unnerving that precisely at this moment, when we have all become sort-of monetarists, the long-scorned Keynesian challenge to monetary policy - the claim that it is ineffective at recession-fighting, because you can’t push on a string - has reemerged as a real issue. So far only Japan has actually found itself in liquidity-trap conditions, but if it has happened once it can happen again, and if it can happen here it presumably can happen elsewhere. So even if Japan does eventually emerge from its slump, the question of how it became trapped and what to do about it remains a pressing one.

In the spring of 1998 I made an effort to apply some modern, intertemporal macroeconomic thinking to the issue of the liquidity trap. The papers I have written since have been controversial, to say the least; and while they have helped stir debate within and outside Japan, have not at time of writing shifted actual policy. Moreover, too much of that debate has been confused, both about what the real issues are and about what I personally have been saying.The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it is a restatement of what I believe to be the essential logic of liquidity-trap economics, with an emphasis in particular on how the "modern" macro I initially used to approach the problem links up with more traditional (and still very useful) IS-LM-type thinking. Second, it attempts to examine in a more or less coherent way the various alternative policies that either are in place or have been proposed to deal with Japan’s liquidity trap, ranging from fiscal stimulus to unconventional open-market operations (and it tries in particular to make clear the difference between the latter and the expectations-focused inflation targeting I have proposed).

1. The liquidity trap: an IS-LM view

Consider the sort of economy introduced a few chapters into most undergraduate macroeconomics books: an economy in which prices are for the moment assumed fixed, meaning both that there can be unemployment because of inadequate nominal demand, and that we need not make a distinction between the nominal and real interest rates. Since the classic 1937 paper by Hicks, it has been usual to summarize short-run equilibrium in such an economy by looking at two curves: a downward sloping IS that shows how lower interest rates increase the demand for goods and hence real output y; and an upward-sloping LM curve that shows how increased output, by increasing the demand for money (whatever exactly that means in the modern world), drives up the interest rate. Monetary policy shifts LM, fiscal policy shifts IS.

Literally from the beginning of IS-LM analysis, however, Hicks realized that monetary policy might in principle be ineffective under "depression" conditions. The reason is that the nominal interest rate cannot be negative - otherwise, cash would dominate bonds as an asset. So at an interest rate near zero the demand for money must become more or less infinitely elastic, implying that the leftmost parts of the LM curve must actually be flat. And suppose that the IS curve happens to intersect LM in that flat region, as it does in Figure 1 . Then changes in the money supply, which move LM back and forth, will have no effect on interest rates or output; monetary policy will be ineffective.

An alternative way to state this possibility is to say that if the interest rate is zero, bonds and money become in effect equivalent assets; so conventional monetary policy, in which money is swapped for bonds via an open-market operation, changes nothing.

I think that it is fair to say that for around two generations - from the point at which it became clear that the 1930s were not about to reemerge, to the belated realization circa 1997 that Japan really was back in a 30s-type monetary environment - nobody thought much about the deeper logic of the liquidity trap. But once it became clear that the Bank of Japan really did consider itself unable to increase demand in an economy that badly needed it, it also became clear (to me at least) that the theory of the liquidity trap needed a fresh, hard look.

I started with a preconception: that the idea of the liquidity trap was basically a red herring, that surely a determined central bank could always reflate the economy. Partly this preconception represented wishful thinking: having engaged in sometimes bitter arguments with "vulgar Keynesians" (e.g. the journalist William Greider (1997)) who believed that spending is always good and saving always bad, I was reluctant to concede that there might be circumstances under which they were right. But it also reflected my intuition - which turned out to be wrong - that the apparent possibility of such a trap in the IS-LM model was an artifact of that model’s intellectual corner-cutting.

The IS-LM framework is, of course, an ad hoc approach that is strategically careless about a number of issues, from price determination, to the consequences of capital accumulation, to the determinants of consumer behavior. Most of the violence in the macro wars of the last generation has focused on aggregate supply; but since one must assume some kind of nominal price rigidity even to get into the discussion of Japan’s demand-side problems, that was not the issue here. Rather, the apparent weakness of IS-LM was in its modeling of aggregate demand.

Here’s how my initial argument - not that different from the debates between Keynes and Pigou - went. In the IS-LM model both the money supply and the price level enter in only one place: on the left-hand side of the money demand equation, which defines a demand for real balances M/P. Monetary policy and changes in the price level therefore affect aggregate demand through the same channel. And to say that increases in M were ineffective beyond some point was therefore equivalent to saying that reductions in P were ineffective in raising demand - that the aggregate demand curve looked something like AD in Figure 2 , downward-sloping over some range but vertical thereafter. And in that case even full price flexibility might not be enough to restore full employment.

But as Pigou pointed out, that simply cannot be right. If nothing else, a fall in the overall price level increases the real value of the public’s holdings of money, and this wealth effect will increase consumption. If the IS-LM model seems to suggest that no full employment equilibrium exists, it is only because that model does not really get the budget constraints right. And it seemed to me that what went for P must go for M; just as a sufficiently large fall in P would always expand the economy to full employment, so must a sufficiently large rise in M. It seemed to me to be a truism that increases in M always raise the equilibrium price level, and hence given a downwardly inflexible price level will always increase output.

To demonstrate the truth of that supposed truism, all that was needed was to write down a model that got the budget constraints right, that did not fudge the individual’s decision problem. So I set out to write down the simplest such model I could. And it ended up saying something quite different.

....[I skipped some of the more mathematical parts, but click on the link to read more.]4. Three causes of a depressed economy

In popular accounts of Japan’s problems one often hears a litany of supposed causes. Some argue that the problem is structural, rooted in both demography (ageing and a declining working-age population) and in waning technological vigor. Others suggest that specific events - in particular, the severity of the collapse of the bubble economy - have jolted Japan into a self-reinforcing spiral of pessimism. Finally, one sometimes hears that the bubble left problems of a more tangible nature, namely large debts that burden enterprises and leave them unable to take advantage even of promising investment opportunities.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the general problem of the liquidity trap, rather than get too much into Japanese specifics, so I can remain agnostic about these differing claims (although as a practical matter I would argue that the cases for both self-fulfilling pessimism and balance-sheet constraints do not hold up very well under critical scrutiny). The point I want to make here is that these are three distinct stories, with different implications for what sorts of policy might work.

The "structural" story is simplest: for whatever reason this economy currently has a high propensity to save, offers limited investment opportunities, and therefore looks like Figure 4. Structural is not a synonym for "immutable", so policy actions could conceivable shift these curves in a favorable direction. However, one would not expect aggregate demand policy to change the fact that the natural rate of interest is negative; all it could do would be to provide a way for the economy to cope with that reality better, that is, without unemployed resources.

The story that attributes a liquidity trap to self-fulfilling pessimism is very different. It is in a fundamental sense a multiple equilibrium story, with the liquidity trap corresponding to the low-level equilibrium. It is easiest to think about this story in terms of a version of the Keynesian cross - a much-maligned device that becomes very useful when the interest rate is fixed because it is hard up against the zero constraint. Figure 6 illustrates a simple multiple-equilibrium story: over some range spending rises more than one-for-one with income. (Why should the relationship flatten out at high and low levels? At high levels resource constraints begin to bind; at low levels the obvious point is that gross investment hits its own zero constraint. There is a largely forgotten literature on this sort of issue, including Hicks (194?), Goodwin (194?), and Tobin (1947)).

The important point about multiple equilibria is that they allow for permanent (or anyway long-lived) effects from temporary policies. There may be excess desired savings even at a zero real interest rate given the pessimism that now prevails in the economy, and that is sustained by the continuing stagnation; but if some policy could push the economy to a high level of output for long enough to change those expectations, the policy would not have to be maintained indefinitely. As we will see, this enlarges the range of policies that could "solve" the problem.

Finally, balance-sheet problems are somewhat different yet again. They may involve an element of self-fulfilling slump: a firm that looks insolvent with an output gap of 10 percent might be reasonably healthy at full employment. But aside from this, balance-sheet problems may be self-correcting given time. If the economy can be put on life support through some kind of temporary policy, this will give firms the chance to pay down their debts, and possibly therefore to regain the ability to invest without support at a later date.

As we will see next, the prospects for many policy options (but not for inflation targeting) depend on which of these stories is most nearly true.

5. Fiscal policy

"Pump-priming" fiscal policy is the conventional answer to a liquidity trap. The classic case is, of course, the way that World War II apparently bootstrapped the United States out of the Great Depression. And in either the IS-LM model or a more sophisticated intertemporal model fiscal expansion will indeed offer short-run relief from a liquidity trap. So why not consider the problem solved? The answer hinges on the government’s own budget constraint.

You might suspect that we are about to talk about Ricardian equivalence here. But that is not the crucial issue. True, if consumers have long time horizons, access to capital markets, and rational expectations tax cuts will not stimulate spending. However, real purchases of goods and services will still create employment, albeit perhaps with a low multiplier. (In a fully Ricardian setup the multiplier on government consumption will be exactly 1: the income generated by the purchases will not lead to higher consumption, because it will be matched by the present value of future tax liabilities). The problem instead is that deficit spending does lead to a large government debt, which will if large enough start to raise questions about solvency.

One might ask why government debt matters if the interest rate is zero in any case. But the liquidity trap, at least in the version I take seriously, is not a permanent state of affairs. Eventually the natural rate of interest will turn positive, and at that point the inherited debt will indeed be a problem.

So is fiscal policy a temporary expedient that cannot serve as a solution to a liquidity trap? Not necessarily: there are two circumstances in which it can work.

First, if the liquidity trap is short-lived in any case, fiscal policy can serve as a bridge. That is, if there are good reasons to believe that after a few years of large deficits monetary policy will again be able to shoulder the load, fiscal stimulus can do its job without posing problems for solvency. This might be the case if there were clear-cut external factors that one could expect to improve - say if the domestic economy was currently depressed because of a severe but probably short-lived financial crisis in trading partners. Or - a possibility argued by some defenders of the current Japanese problem - temporary fiscal support might provide the breathing space during which firms get their balance sheets in order.

If you listen to the rhetoric of fiscal policy, however - all the talk about pump-priming, jump-starting, etc. - it becomes clear that many people implicitly believe that only a temporary fiscal stimulus is necessary because it will jolt the economy into a higher equilibrium. Thus in Figure 5 a policy that shifts the spending curve up sufficiently will eliminate the low-level equilibrium; if the policy is sustained long enough, when it is removed the economy will settle into the high-level equilibrium instead.

If this is the underlying model of how fiscal policy is supposed to succeed, however, one must realize that the criterion for success is quite strong. It is not enough for fiscal expansion to produce growth - that will happen even if the liquidity trap is deeply structural in nature. Rather, it must lead to large increases in private demand, so large that the economy begins a self-sustaining process of recovery that can continue without further stimulus.

It is in this light that one should read economic reports about Japan today, and perhaps about other troubled economies in the future. For what it is worth, at the time of writing there is nothing in the data that would suggest that anything like the supposed shift to a higher equilibrium is in progress. Indeed, private demand is actually falling, with more than all the growth coming from government demand.

None of this should be read as a reason to abandon fiscal stimulus - in fact, one shudders to think what would happen if Japan were not to provide further packages as the current one expires. But fiscal stimulus is a solution, rather than a way of buying time, only under some particular assumptions that are at the very least rather speculative.

6. Varieties of monetary policy

If fiscal policy is not a definitive answer, we turn to monetary policy. As I have tried to argue, the most basic models of a liquidity trap already imply that a credible commitment to future monetary expansion is the "correct" answer to a liquidity trap, in the sense that – like monetary expansion in the face of a conventional recession – it is a way of replicating the results the economy would achieve if it had perfectly flexible prices. But this notion of monetary policy has become confused with two other monetary proposals, "quantitative easing" and unconventional open-market operations; it is important to be aware that these are not the same thing, and rest on different assumptions about what is needed.

Quantitative easing: There has been extensive discussion of "quantitative easing" , which usually means urging the central bank simply to impose high rates of increase in the monetary base. Some variants argue that the central bank should also set targets for broader aggregates such as M2. The Bank of Japan has repeatedly argued against such easing, arguing that it will be ineffective – that the excess liquidity will simply be held by banks or possibly individuals, with no effect on spending – and has often seemed to convey the impression that this is an argument against any kind of monetary solution.

It is, or should be, immediately obvious from our analysis that in a direct sense the BOJ argument is quite correct. No matter how much the monetary base increases, as long as expectations are not affected it will simply be a swap of one zero-interest asset for another, with no real effects. A side implication of this analysis (see Krugman 1998) is that the central bank may literally be unable to affect broader monetary aggregates: since the volume of credit is a real variable, and like everything else will be unaffected by a swap that does not change expectations, aggregates that consist mainly of inside money that is the counterpart of credit may be as immune to monetary expansion as everything else.

But this argument against the effectiveness of quantitative easing is simply irrelevant to arguments that focus on the expectational effects of monetary policy. And quantitative easing could play an important role in changing expectations; a central bank that tries to promise future inflation will be more credible if it puts its (freshly printed) money where its mouth is.

Unconventional open-market operations: A second argument on monetary policy is that while conventional open-market operations are ineffective, the central bank can still gain traction by engaging in unconventional operations – with the most obvious ones being either currency-market interventions or purchases of longer-term securities. The argument of proponents of such moves, for example Alan Meltzer, is that in reality foreign bonds and long-term domestic bonds are not perfect substitutes for short-term assets, and hence open-market operations in these assets can expand the economy by driving the currency and the long-term interest rate down.

Clearly there is something to this argument: perfect substitutability is a helpful modeling simplification, but the real world is more complicated. And in the absence of perfect substitution, these interventions will clearly have some effect. The question is how much effect – or, to put it a bit differently, how large would the BOJ’s purchases of dollars and/or JGBs have to be to make an important contribution to economic recovery. (You might say that it doesn’t matter – the BOJ can print as many yen as it likes. And perhaps that is the right thing to say in principle. But if supporting the economy requires that the BOJ acquire, say, 100 trillion yen in assets over the next four years – and if it is likely to lose money on those assets – the policy is going to be difficult to pursue).

A rigorous model of monetary policy in the face of imperfect substitution is difficult to construct (if only because one must derive that imperfection somehow). But a shortcut may be useful. Consider, then, the case of foreign exchange intervention – purchasing foreign bonds in an effort to bid down the currency. And let us look back at Figure 5, which illustrates how a liquidity trap can occur even in an open economy, because the desired capital export even at a zero interest rate will be less than the excess of domestic savings over investment.

What would the central bank be doing if it engages in exchange-market intervention in such a situation? The answer is that in effect it would be trying to do through its own operations the capital export that the private sector is unwilling to do. So a minimum estimate of the size of intervention needed per year is "enough to close the gap" – that is, the central bank would have to buy enough foreign exchange , i.e. export enough capital, to close the ex ante gap between S-I and NX at a zero interest rate. In practice, the intervention would have to be substantially larger than this, probably several times as large, because the intervention would induce private flows in the opposite direction. (An intervention that weakens the yen reinforces the incentive for private investors to bet on its future appreciation).

Here is some sample arithmetic: suppose that you believe that Japan currently has an output gap of 10 percent, which might be the result of an ex ante savings surplus of 4 or 5 percent of GDP. Then intervention in the foreign exchange market sufficient to close that gap would have to be several times as large as the savings surplus – i.e., it could involve the Bank of Japan acquiring foreign assets at the rate of 10, 15 or more percent of GDP, over an extended period. (Incidentally, does it matter if the interventions are unsterilized? Well, an unsterilized intervention is a sterilized intervention plus quantitative easing; the latter part makes no difference unless it affects expectations).

Purchases of long-term bonds would work similarly. In this case the central bank would in effect be competing with private investors as a source of investment finance (this would be true even if the intervention itself were in government bonds). Again, there would be an offset – with lower yields, private investors would divert some of their savings from bonds into short term assets or, what is equivalent under liquidity trap conditions, cash. So again the central bank would have to sustain purchases at a rate several times the ex ante savings-investment gap; in this case the BOJ might find itself purchasing long-term bonds at a rate of 10-15 or more percent of GDP.

There are obvious political economy problems with such actions. The prospect of having a quasi-governmental institution owning a trillion dollars of overseas assets, or most of the Japanese government’s debt, is a bit daunting. Of course this would not happen if a relatively brief period of unconventional monetary policy led to a self-sustaining recovery. But to believe in this prospect you must, as in the case of fiscal policy, believe that the economy is currently in a low-level equilibrium and can be jolted back to prosperity with temporary actions – a fairly exotic, though not necessarily wrong, view on which to base policy.

The same remarks applied to fiscal policy also apply here: while unconventional open-market operations are less certain a cure than their proponents seem to think, they could help, and might well be part of a realistic strategy.

Expectations: Finally, we return to the issue of inflation targeting. The basic point, once again, is that a credible commitment to expand the future money supply, perhaps via an inflation target, will be expansionary even in a liquidity trap. There are two problems, however, with this view. One is that it is not enough to get central bankers to change their spots; one must also convince the market that the spots have changed, that is, actually change expectations. The truth is that economic theory does not offer a clear answer to how to make this happen. One might well argue, however, that one way to help make a commitment to do something unusual credible is to do a lot of other unusual things, demonstrating unambiguously that the central bank does understand that it is living in a different world. Market participants are pretty much unanimous in their belief that unsterilized intervention would have a much bigger effect than sterilized, essentially because it would convey news about future BOJ policy; the same could be said of other actions, including quantitative easing. My personal view is that a country deep in a liquidity trap should try everything, even if careful analysis says that some of the actions should not matter; if, in the precise if annoying phrase I used in my first paper on the liquidity trap, a central bank must "credibly promise to be irresponsible", it should waste no opportunity to demonstrate its new spirit.

The other problem is that the policy shift must not only be credible but sufficiently large. A too-modest inflation target will turn into a self-defeating prophecy. Suppose that the central bank successfully convinces everyone that there will henceforth be 1 percent inflation – but that a real interest rate of minus 1 percent is not low enough to restore full employment. Then despite the expectational change, the economy will remain subject to deflationary pressure, and the policy will fail. Half a loaf, in other words, can be worse than none.

7. Concluding remarks

The whole subject of the liquidity trap has a sort of Alice-through-the-looking-glass quality. Virtues like saving, or a central bank known to be strongly committed to price stability, become vices; to get out of the trap a country must loosen its belt, persuade its citizens to forget about the future, and convince the private sector that the government and central bank aren’t as serious and austere as they seem.

The strangeness of the situation extends to policy discussion. Because the usual rules do not apply, conventional rules of thumb about policy become hard to justify. We usually imagine that policy is more or less based on conventional models – in particular, that normally policy will be based on the simple, rather dull models in the textbooks rather than exotic stories that might be true but probably aren’t. In the case of the liquidity trap, however, conventional textbook models imply unconventional policy conclusions – for inflation targeting is not an exotic idea but the natural implication of both IS-LM and modern intertemporal models applied to this unusual situation.To defend the conventional policy wisdom one must therefore appeal to various unorthodox models – supply curves that slope down, demand curves that slope up, multiple equilibria, etc.. So unworldly economists become defenders of analytical orthodoxy, while the dignified men in suits become devotees of exotic theories.

What I hope that I have done in this paper is to make clear how conventional the logic behind seemingly radical proposals like inflation targeting really is, and conversely how hard it is to rationalize what still passes for sensible policies among many officials. Let’s see it it works this time around.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Chart: The Collapse In Global Trade - Planet Money Blog : NPR

"The big elephant in the room." (Carl Weinberg/High Frequency Economics)

I've been waiting for a paper like this

Steve Kaplan and Joshua Rauh write:

"...the top 25 hedge fund managers combined appear to have earned more than all 500 S&P 500 CEOs combined (both realized and estimated)."

Here is the link, here is the non-gated version.

...there is no evidence of a change in social norms on Wall Street. What has changed is the amount of money managed and the concomitant amount of pay.

There is a great deal of analysis and information (though to me, not many surprises) in this important paper. The authors also find no link between higher pay and the relation of a sector to international trade.

America’s Chinese disease

...the Fed is engaged in massive “quantitative easing” — a misleading term, but I guess we’re stuck with it. What it basically means is that the Fed is selling Treasury bills or their equivalent (interest-paying excess bank reserves are essentially the same thing), while buying other assets, expanding its balance sheet enormously in the process.What kinds of other assets? Mortgage-backed securities; securities backed by credit-card debt; longer-term government debt; etc..

One type of asset the Fed has not been buying is foreign short-term securities. But that’s not because such purchases would be ineffective. On the contrary, selling domestic short-term debt and buying its foreign-currency counterpart is the essence of a sterilized foreign-exchange-market intervention, which is a time-honored way of gaining a competitive advantage and helping your economy expand.

And some countries have, in fact, made foreign-currency purchases a part of their quantitative easing strategy — Switzerland in particular. The only reason the Fed isn’t doing this is that we’re a big player, and can’t be seen to be pursuing a beggar-thy-neighbor strategy.

But now ask the question: what would the effect be if China decided to sell a chunk of its Treasury bill holdings and put them in other currencies? The answer is that China would, in effect, be engaging in quantitative easing on behalf of the Fed. The Chinese would be doing us a favor! (And doing the Europeans and Japanese a lot of harm.)

Conversely, by continuing to buy dollars, the Chinese are in effect undermining part of the Fed’s efforts — they’re conducting quantitative diseasing, I guess you could say, hence the title of this post.

The point is that right now the United States has nothing to fear from Chinese threats to diversify out of the dollar. On the contrary, if the Chinese do decide to start selling dollars, Tim Geithner and Ben Bernanke should send them a nice thank-you note.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Aid Fueled Latest Surge on Wall Street

1. Bankruptcy in which the banks do not fully pay back what they owe. The problem is that when big banks do this, the entire financial system would freeze up which was already starting to happen. This is why some banks are "too big to fail."

2. Give the banks money. This was Paulson's original plan. He wanted to buy the "toxic assets" for more than they were worth. None of the TARP money actually bought any toxic (or "troubled") assets even though the first two letters of the acronym stand for "troubled asset".

3. Loan the banks money at low interest rates and guarantee the bank debt. This was what the Paulson Plan did. The idea is for the banks to be able to keep making profitable loans at higher interest rates and thereby make enough profits to restore their capital.

4. Give the banks money by buying their stock. This was decried as socialism and/or nationalism because it would mean that the government would own a majority of some of the sickest banks, but all the other options except #1 were socialist too and this option has the advantage that the taxpayers could get their money back (when stock values are restored with the health of the banks) rather than the bank owners and managers getting much of the profits of the bailout as is now happening.

Because we went with option #3, the banks are now making big profits which was what the TARP plan hoped would happen. Unfortunately, the banks are not loaning much money to small businesses who are the main drivers of employment growth at the end of recessions. The big banks are finding it more profitable to use their low-interest government-subsidized money to make risky bets on the financial markets instead and why not? What do they have to lose?

NYTimes.com:

Many of the steps that policy makers took last year to stabilize the financial system — reducing interest rates to near zero, bolstering big banks with taxpayer money, guaranteeing billions of dollars of financial institutions’ debts — helped set the stage for this new era of Wall Street wealth.

Titans like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase are making fortunes in hot areas like trading stocks and bonds, rather than in the ho-hum business of lending people money. They also are profiting by taking risks that weaker rivals are unable or unwilling to shoulder — a benefit of less competition after the failure of some investment firms last year.

So even as big banks fight efforts in Congress to subject their industry to greater regulation — and to impose some restrictions on executive pay — Wall Street has Washington to thank in part for its latest bonanza.

...A year after the crisis struck, many of the industry’s behemoths — those institutions deemed too big to fail — are, in fact, getting bigger, not smaller. For many of them, it is business as usual. Over the last decade the financial sector was the fastest-growing part of the economy, with two-thirds of growth in gross domestic product attributable to incomes of workers in finance.

Now, the industry has new tools at its disposal, courtesy of the government.

With interest rates so low, banks can borrow money cheaply and put those funds to work in lucrative ways, whether using the money to make loans to companies at higher rates, or to speculate in the markets. Fixed-income trading — an area that includes bonds and currencies — has been particularly profitable.

“Robust trading results led the way,” said Howard Chen, a banking analyst at Credit Suisse, describing the latest profits.

...A big reason for Goldman Sachs’s blowout profits this year has been the willingness of its traders to take big risks — they have put more money on the line while other banks that suffered last year have reined in such moves. Executives say there are big strategic gaps opening up between banks on Wall Street that are taking on more risks, and those that are treading a safer path.

Banks that have waded back into the markets have been able to exploit large gaps in the prices of various investments, a feature of the postcrisis financial markets. The so-called bid-ask spreads — the difference between the price at which banks are willing to buy things like bonds, and the price at which they are willing to sell — are roughly twice what they were two years ago.

As Goldman Gloats, What Does It Matter For Us?

NPR: "Should we care about Goldman's profits and compensation? It's pretty gauche when your take-home pay is millions of dollars while some of your neighbors can't find work. But is it wrong? Is it something those of us on the outside should care about?

Normally, I'd say it's nobody's business. What people get paid is best left to the marketplace.

But Goldman Sachs is different because those of us on the outside are really on the inside. Goldman Sachs was propped up with our money. Not the money it took directly from the government and paid back. The money that AIG gave it that really came from the taxpayer.

Goldman Sachs being proud of its performance this year is like the Harlem Globetrotters bragging that they went undefeated. It's not really a normal competition.

Goldman Sachs played the same game as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers — they made lousy investments financed with borrowed money. When the assets fell in value, Bear and Lehman died. They were reckless with other people's money.

But Goldman Sachs is still here, Why?

Part of the reason is that maybe it took a little less risk and maybe hedged against that risk a little better. But part of the reason Goldman lives and thrives is that the government bailed out AIG. Almost 13 billion dollars of the money the government sent to AIG went out the door and over to Goldman Sachs. This money included loans and insurance Goldman bought on its bad bets. Some of that insurance turned out to be a bad bet, too. But Goldman didn't bear the cost. The taxpayers did."

Friday, October 16, 2009

When should the Fed raise rates? (even more wonkish) - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Greenspan Says U.S. Should Consider Breaking Up Large Banks

Oct. 15 (Bloomberg) -- U.S. regulators should consider breaking up large financial institutions considered “too big to fail,” former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said.I don't know how the government is supposed to break up the banks again. Greenspan probably could have prevented a lot of the mergers that created the superbanks, but now I think there is a more elegant way. When there is an externality, it can be corrected with a Pigouvian tax. The oversized banks impose an external cost on society and so they should be taxed at a higher rate than smaller banks. And if the tax is high enough, then the big banks will divide up of their own accord. If they have enough economies of scale, then they can stay big, but at least they will be paying back some of their dues to society.

Those banks have an implicit subsidy allowing them to borrow at lower cost because lenders believe the government will always step in to guarantee their obligations. That squeezes out competition and creates a danger to the financial system, Greenspan told the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

“If they’re too big to fail, they’re too big,” Greenspan said today. “In 1911 we broke up Standard Oil -- so what happened? The individual parts became more valuable than the whole. Maybe that’s what we need to do.”

Sunday, October 11, 2009

When should the Fed raise rates?

Friday, October 9, 2009

Econbrowser: Trade Procyclicality in the Current Recession: The View from the US

the current pace of trade activity as worse than that during the Great Depression.First, let's take a look at the exports-to-GDP and imports-to-GDP ratios.

Figure 1: Non-agricultural goods exports to GDP ratio (blue), and non-oil goods imports to GDP ratio (red). NBER recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, GDP 2009Q2 3rd release of 30 Sep 2009, NBER, and author's calculations.

Gold Standard Questions

What individuals or institutions are the biggest owners of the world's gold?

What would happen to the size of the world money supply if the entire world went back on the gold standard?

What are some economic problems with the gold standard?

What are some economic advantages of the gold standard?

Some libertarians like Alan Greenspan in the 1960s and Ron Paul today favor a return to the gold standard. What might be a political (rather than economic) reason libertarians tend to favor the gold standard more than others?

Capital Controls: Theory and Practice

Capital Controls: Theory and Practice:

"Among the economists promoting capital controls, Keynes was the most prominent. He was in favor of controls as a protective tool from the unstable international economy and the possibility of capital flight, which, among other things, causes a decrease in potential growth, erosion in the tax base, and redistribution from poorer to richer groups. From 1945-60 capital controls were unquestioned. During the immediate postwar period, freedom of capital movements was hardly an issue; international flows of capital through markets were unthinkable. The memories of the hectic 1920s and 1930s were still present and strict controls on international capital movements were needed for financial stability. According to Shafer (1995), developments at the end of the 1950's and early 1960's questioned the logic of the so-called Bretton Woods’ dichotomy, that is, controls for finance and freedom for trade. Capital account liberalization was taken seriously with the establishment of the OECD in 1961."

Warning: Capital Controls Are in Your Future

When Jim Rogers taught classes at Columbia, he liked to tell students that the US had a proud history of implementing capital controls, and warned them against going on the merry assumption that it would ever and always be easy to make cross-border investments. For instance, taxes on foreign securities transactins are a soft form of control and have been used to facilitate or restrict cross-border capital flows. The US lowered them when it abandoned Bretton Woods in 1971 to aid in adjustment of the price of the greenback.