Motor vehicles added a whopping 1.66% of the 3.5% growth in Q3 GDP. More specifically, motor vehicle output was up... wait for it... 157.6% on an annualized basis.

Search This Blog

Thursday, October 29, 2009

EconomPic: Thank You Cash for Clunkers

Growth and jobs

Just a quick note on the GDP report. Obviously, 3.5 percent growth is a lot better than shrinkage. But it’s not enough — not remotely enough — to make any real headway against the unemployment problem. Here’s the scatterplot of annual growth versus annual changes in the unemployment rate over the past 60 years:Basically, we’d be lucky if growth at this rate brought unemployment down by half a percentage point per year. At this rate, we wouldn’t reach anything that feels like full employment until well into the second Palin administration.BEA, BLS

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

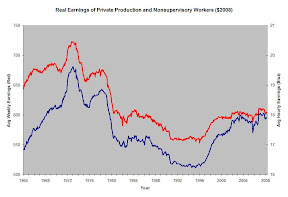

Real Earnings, Not So Much

The discrepancy between the series is the change in hours over this period--the series for average weekly earnings falls over the period because hours fall more than enough to offset the slight rise in average hourly earnings. Over this period, private employment has been a fairly constant share of total nonfarm employment (a bit more than 80%) and production and non-supervsory employment has been a fairly constant share of total private employment (

This is one of the most depressing graphs I've ever seen.

LABOR'S SHARE

This shift to an environment of stronger productivity and weaker real growth generated an interesting development that has received little attention among economists or in the business press.

This development was a secular decline in labor's share of the pie. Prior to the 1982 recession there was a strong cyclical pattern of labor's but it was around a long term or secular flat trend. But since the early 1980s labor's share of the pie has fallen sharply by about ten percentage points. Note that the chart is of labor compensation divided by nominal output indexed to 1992 = 100. That is because the data for each series is reported as an index number at 1992=100 rather than in dollar terms. So the scale is set to 1992 =100 rather than in percentage points. But it still shows that labor payments as a share of nonfarm business total ouput has declined sharply over the last 20 years and prior to the latest cycle we did not even see the normal late cycle uptick in labor's share.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Adjustment and the dollar

...imagine what the world might look like if it (1) returns to more or less full employment (2) experiences a significant reduction in imbalances — in particular, a much lower US trade deficit.

For (2) to happen, the US must start spending more within its means; overall spending will have to fall relative to GDP. Correspondingly, spending in the rest of the world must rise.

But that’s not the end of the story. Suppose that spending in the United States falls by $500 billion, while spending in the rest of the world rises by $500 billion. Other things equal, most of that decline in US spending would fall on US-produced goods and services. Remember, even if you buy Chinese stuff at Walmart, much of the price represents US distribution and retailing costs. The world, you might say, is a long way from being truly flat.Meanwhile, a much smaller fraction of the rise in spending abroad will fall on US products. So other things equal, this reallocation of spending would lead to an excess supply of US goods and services, an excess demand for goods and services produced elsewhere. (Trade economists know that I’m talking about the transfer problem.)

So something has to give — specifically, the relative price of US output, and along with it such things as US relative wages, has to fall.

There are three ways this could happen: (1) deflation in the United States (2) inflation in the rest of the world (3) a depreciation of the dollar against other currencies. Leave (2) aside, on the grounds that central banks will fight it. Then the choice is between (1) and (3).

And here’s the thing: deflation is hard (ask Spain), because prices are sticky in nominal terms. How do we know that? Lots of evidence. See, for example, A Sticky Price Manifesto by Larry Ball and some guy named Mankiw. But the most compelling evidence — familiar to international macro people, but oddly uncited by most domestic macroeconomists — comes from exchange rates.

The first person to make this point was probably none other than Milton Friedman (cue Brad DeLong on the decline of the Chicago School), but the really influential quantitative analysis was by Michael Mussa.

Mussa pointed out that a funny thing happens when countries move from fixed to floating exchange rates: the nominal exchange rate becomes much more variable, of course, but so does the real exchange rate — the exchange rate adjusted for price levels. Meanwhile, relative inflation rates remain within a narrow band. The obvious interpretation is that once the exchange rate is freed, it bounces around a lot, while domestic prices in domestic currency are sticky, and don’t move much.

Here’s an updated version of Mussa’s point. The top figure shows quarterly log changes in the US-Germany real exchange rate; the bottom figure divides this into nominal exchange rate changes and inflation differentials. The Mussa point is crystal clear.

So, the bottom line: to narrow international imbalances, we need a lower relative price of US output. Because prices are sticky, by far the easiest way to get there is dollar depreciation.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Matthew Yglesias » Another Spin at the Wheel

The way this works is that you identify arbitrage opportunities such that you make trades you’re overwhelmingly likely to make money on. But those opportunities only exist because the opportunities are very small. So to make them worth pursuing, you need to lever-up with huge amounts of debt. Which means that on the rare moments when the trades do go bad, everything falls apart: “The strategy typically has a high ‘blow-up’ risk because of the large amounts of leverage it uses to profit from often tiny pricing anomalies.”

As a friend puts it, this strategy is “literally the equivalent of putting a chip on 35 of the 36 roulette numbers and hoping for no zero/36.” But you’re doing it with borrowed money. I’m not a huge believer in human rationality, so I totally understand how this scam worked once. That he was able to get a second fund off the ground is pretty amazing."

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Thinking about the liquidity trap

Krugman 1999:

We live in the Age of the Central Banker - an era in which Greenspan, Duisenberg, and Hayami are household words, in which monetary policy is generally believed to be so effective that it cannot safely be left in the hands of politicians who might use it to their advantage. Through much of the world, quasi-independent central banks are now entrusted with the job of steering economies between the rocks of inflation and the whirlpool of deflation. Their judgement is often questioned, but their power is not.

It is therefore ironic as well as unnerving that precisely at this moment, when we have all become sort-of monetarists, the long-scorned Keynesian challenge to monetary policy - the claim that it is ineffective at recession-fighting, because you can’t push on a string - has reemerged as a real issue. So far only Japan has actually found itself in liquidity-trap conditions, but if it has happened once it can happen again, and if it can happen here it presumably can happen elsewhere. So even if Japan does eventually emerge from its slump, the question of how it became trapped and what to do about it remains a pressing one.

In the spring of 1998 I made an effort to apply some modern, intertemporal macroeconomic thinking to the issue of the liquidity trap. The papers I have written since have been controversial, to say the least; and while they have helped stir debate within and outside Japan, have not at time of writing shifted actual policy. Moreover, too much of that debate has been confused, both about what the real issues are and about what I personally have been saying.The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it is a restatement of what I believe to be the essential logic of liquidity-trap economics, with an emphasis in particular on how the "modern" macro I initially used to approach the problem links up with more traditional (and still very useful) IS-LM-type thinking. Second, it attempts to examine in a more or less coherent way the various alternative policies that either are in place or have been proposed to deal with Japan’s liquidity trap, ranging from fiscal stimulus to unconventional open-market operations (and it tries in particular to make clear the difference between the latter and the expectations-focused inflation targeting I have proposed).

1. The liquidity trap: an IS-LM view

Consider the sort of economy introduced a few chapters into most undergraduate macroeconomics books: an economy in which prices are for the moment assumed fixed, meaning both that there can be unemployment because of inadequate nominal demand, and that we need not make a distinction between the nominal and real interest rates. Since the classic 1937 paper by Hicks, it has been usual to summarize short-run equilibrium in such an economy by looking at two curves: a downward sloping IS that shows how lower interest rates increase the demand for goods and hence real output y; and an upward-sloping LM curve that shows how increased output, by increasing the demand for money (whatever exactly that means in the modern world), drives up the interest rate. Monetary policy shifts LM, fiscal policy shifts IS.

Literally from the beginning of IS-LM analysis, however, Hicks realized that monetary policy might in principle be ineffective under "depression" conditions. The reason is that the nominal interest rate cannot be negative - otherwise, cash would dominate bonds as an asset. So at an interest rate near zero the demand for money must become more or less infinitely elastic, implying that the leftmost parts of the LM curve must actually be flat. And suppose that the IS curve happens to intersect LM in that flat region, as it does in Figure 1 . Then changes in the money supply, which move LM back and forth, will have no effect on interest rates or output; monetary policy will be ineffective.

An alternative way to state this possibility is to say that if the interest rate is zero, bonds and money become in effect equivalent assets; so conventional monetary policy, in which money is swapped for bonds via an open-market operation, changes nothing.

I think that it is fair to say that for around two generations - from the point at which it became clear that the 1930s were not about to reemerge, to the belated realization circa 1997 that Japan really was back in a 30s-type monetary environment - nobody thought much about the deeper logic of the liquidity trap. But once it became clear that the Bank of Japan really did consider itself unable to increase demand in an economy that badly needed it, it also became clear (to me at least) that the theory of the liquidity trap needed a fresh, hard look.

I started with a preconception: that the idea of the liquidity trap was basically a red herring, that surely a determined central bank could always reflate the economy. Partly this preconception represented wishful thinking: having engaged in sometimes bitter arguments with "vulgar Keynesians" (e.g. the journalist William Greider (1997)) who believed that spending is always good and saving always bad, I was reluctant to concede that there might be circumstances under which they were right. But it also reflected my intuition - which turned out to be wrong - that the apparent possibility of such a trap in the IS-LM model was an artifact of that model’s intellectual corner-cutting.

The IS-LM framework is, of course, an ad hoc approach that is strategically careless about a number of issues, from price determination, to the consequences of capital accumulation, to the determinants of consumer behavior. Most of the violence in the macro wars of the last generation has focused on aggregate supply; but since one must assume some kind of nominal price rigidity even to get into the discussion of Japan’s demand-side problems, that was not the issue here. Rather, the apparent weakness of IS-LM was in its modeling of aggregate demand.

Here’s how my initial argument - not that different from the debates between Keynes and Pigou - went. In the IS-LM model both the money supply and the price level enter in only one place: on the left-hand side of the money demand equation, which defines a demand for real balances M/P. Monetary policy and changes in the price level therefore affect aggregate demand through the same channel. And to say that increases in M were ineffective beyond some point was therefore equivalent to saying that reductions in P were ineffective in raising demand - that the aggregate demand curve looked something like AD in Figure 2 , downward-sloping over some range but vertical thereafter. And in that case even full price flexibility might not be enough to restore full employment.

But as Pigou pointed out, that simply cannot be right. If nothing else, a fall in the overall price level increases the real value of the public’s holdings of money, and this wealth effect will increase consumption. If the IS-LM model seems to suggest that no full employment equilibrium exists, it is only because that model does not really get the budget constraints right. And it seemed to me that what went for P must go for M; just as a sufficiently large fall in P would always expand the economy to full employment, so must a sufficiently large rise in M. It seemed to me to be a truism that increases in M always raise the equilibrium price level, and hence given a downwardly inflexible price level will always increase output.

To demonstrate the truth of that supposed truism, all that was needed was to write down a model that got the budget constraints right, that did not fudge the individual’s decision problem. So I set out to write down the simplest such model I could. And it ended up saying something quite different.

....[I skipped some of the more mathematical parts, but click on the link to read more.]4. Three causes of a depressed economy

In popular accounts of Japan’s problems one often hears a litany of supposed causes. Some argue that the problem is structural, rooted in both demography (ageing and a declining working-age population) and in waning technological vigor. Others suggest that specific events - in particular, the severity of the collapse of the bubble economy - have jolted Japan into a self-reinforcing spiral of pessimism. Finally, one sometimes hears that the bubble left problems of a more tangible nature, namely large debts that burden enterprises and leave them unable to take advantage even of promising investment opportunities.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the general problem of the liquidity trap, rather than get too much into Japanese specifics, so I can remain agnostic about these differing claims (although as a practical matter I would argue that the cases for both self-fulfilling pessimism and balance-sheet constraints do not hold up very well under critical scrutiny). The point I want to make here is that these are three distinct stories, with different implications for what sorts of policy might work.

The "structural" story is simplest: for whatever reason this economy currently has a high propensity to save, offers limited investment opportunities, and therefore looks like Figure 4. Structural is not a synonym for "immutable", so policy actions could conceivable shift these curves in a favorable direction. However, one would not expect aggregate demand policy to change the fact that the natural rate of interest is negative; all it could do would be to provide a way for the economy to cope with that reality better, that is, without unemployed resources.

The story that attributes a liquidity trap to self-fulfilling pessimism is very different. It is in a fundamental sense a multiple equilibrium story, with the liquidity trap corresponding to the low-level equilibrium. It is easiest to think about this story in terms of a version of the Keynesian cross - a much-maligned device that becomes very useful when the interest rate is fixed because it is hard up against the zero constraint. Figure 6 illustrates a simple multiple-equilibrium story: over some range spending rises more than one-for-one with income. (Why should the relationship flatten out at high and low levels? At high levels resource constraints begin to bind; at low levels the obvious point is that gross investment hits its own zero constraint. There is a largely forgotten literature on this sort of issue, including Hicks (194?), Goodwin (194?), and Tobin (1947)).

The important point about multiple equilibria is that they allow for permanent (or anyway long-lived) effects from temporary policies. There may be excess desired savings even at a zero real interest rate given the pessimism that now prevails in the economy, and that is sustained by the continuing stagnation; but if some policy could push the economy to a high level of output for long enough to change those expectations, the policy would not have to be maintained indefinitely. As we will see, this enlarges the range of policies that could "solve" the problem.

Finally, balance-sheet problems are somewhat different yet again. They may involve an element of self-fulfilling slump: a firm that looks insolvent with an output gap of 10 percent might be reasonably healthy at full employment. But aside from this, balance-sheet problems may be self-correcting given time. If the economy can be put on life support through some kind of temporary policy, this will give firms the chance to pay down their debts, and possibly therefore to regain the ability to invest without support at a later date.

As we will see next, the prospects for many policy options (but not for inflation targeting) depend on which of these stories is most nearly true.

5. Fiscal policy

"Pump-priming" fiscal policy is the conventional answer to a liquidity trap. The classic case is, of course, the way that World War II apparently bootstrapped the United States out of the Great Depression. And in either the IS-LM model or a more sophisticated intertemporal model fiscal expansion will indeed offer short-run relief from a liquidity trap. So why not consider the problem solved? The answer hinges on the government’s own budget constraint.

You might suspect that we are about to talk about Ricardian equivalence here. But that is not the crucial issue. True, if consumers have long time horizons, access to capital markets, and rational expectations tax cuts will not stimulate spending. However, real purchases of goods and services will still create employment, albeit perhaps with a low multiplier. (In a fully Ricardian setup the multiplier on government consumption will be exactly 1: the income generated by the purchases will not lead to higher consumption, because it will be matched by the present value of future tax liabilities). The problem instead is that deficit spending does lead to a large government debt, which will if large enough start to raise questions about solvency.

One might ask why government debt matters if the interest rate is zero in any case. But the liquidity trap, at least in the version I take seriously, is not a permanent state of affairs. Eventually the natural rate of interest will turn positive, and at that point the inherited debt will indeed be a problem.

So is fiscal policy a temporary expedient that cannot serve as a solution to a liquidity trap? Not necessarily: there are two circumstances in which it can work.

First, if the liquidity trap is short-lived in any case, fiscal policy can serve as a bridge. That is, if there are good reasons to believe that after a few years of large deficits monetary policy will again be able to shoulder the load, fiscal stimulus can do its job without posing problems for solvency. This might be the case if there were clear-cut external factors that one could expect to improve - say if the domestic economy was currently depressed because of a severe but probably short-lived financial crisis in trading partners. Or - a possibility argued by some defenders of the current Japanese problem - temporary fiscal support might provide the breathing space during which firms get their balance sheets in order.

If you listen to the rhetoric of fiscal policy, however - all the talk about pump-priming, jump-starting, etc. - it becomes clear that many people implicitly believe that only a temporary fiscal stimulus is necessary because it will jolt the economy into a higher equilibrium. Thus in Figure 5 a policy that shifts the spending curve up sufficiently will eliminate the low-level equilibrium; if the policy is sustained long enough, when it is removed the economy will settle into the high-level equilibrium instead.

If this is the underlying model of how fiscal policy is supposed to succeed, however, one must realize that the criterion for success is quite strong. It is not enough for fiscal expansion to produce growth - that will happen even if the liquidity trap is deeply structural in nature. Rather, it must lead to large increases in private demand, so large that the economy begins a self-sustaining process of recovery that can continue without further stimulus.

It is in this light that one should read economic reports about Japan today, and perhaps about other troubled economies in the future. For what it is worth, at the time of writing there is nothing in the data that would suggest that anything like the supposed shift to a higher equilibrium is in progress. Indeed, private demand is actually falling, with more than all the growth coming from government demand.

None of this should be read as a reason to abandon fiscal stimulus - in fact, one shudders to think what would happen if Japan were not to provide further packages as the current one expires. But fiscal stimulus is a solution, rather than a way of buying time, only under some particular assumptions that are at the very least rather speculative.

6. Varieties of monetary policy

If fiscal policy is not a definitive answer, we turn to monetary policy. As I have tried to argue, the most basic models of a liquidity trap already imply that a credible commitment to future monetary expansion is the "correct" answer to a liquidity trap, in the sense that – like monetary expansion in the face of a conventional recession – it is a way of replicating the results the economy would achieve if it had perfectly flexible prices. But this notion of monetary policy has become confused with two other monetary proposals, "quantitative easing" and unconventional open-market operations; it is important to be aware that these are not the same thing, and rest on different assumptions about what is needed.

Quantitative easing: There has been extensive discussion of "quantitative easing" , which usually means urging the central bank simply to impose high rates of increase in the monetary base. Some variants argue that the central bank should also set targets for broader aggregates such as M2. The Bank of Japan has repeatedly argued against such easing, arguing that it will be ineffective – that the excess liquidity will simply be held by banks or possibly individuals, with no effect on spending – and has often seemed to convey the impression that this is an argument against any kind of monetary solution.

It is, or should be, immediately obvious from our analysis that in a direct sense the BOJ argument is quite correct. No matter how much the monetary base increases, as long as expectations are not affected it will simply be a swap of one zero-interest asset for another, with no real effects. A side implication of this analysis (see Krugman 1998) is that the central bank may literally be unable to affect broader monetary aggregates: since the volume of credit is a real variable, and like everything else will be unaffected by a swap that does not change expectations, aggregates that consist mainly of inside money that is the counterpart of credit may be as immune to monetary expansion as everything else.

But this argument against the effectiveness of quantitative easing is simply irrelevant to arguments that focus on the expectational effects of monetary policy. And quantitative easing could play an important role in changing expectations; a central bank that tries to promise future inflation will be more credible if it puts its (freshly printed) money where its mouth is.

Unconventional open-market operations: A second argument on monetary policy is that while conventional open-market operations are ineffective, the central bank can still gain traction by engaging in unconventional operations – with the most obvious ones being either currency-market interventions or purchases of longer-term securities. The argument of proponents of such moves, for example Alan Meltzer, is that in reality foreign bonds and long-term domestic bonds are not perfect substitutes for short-term assets, and hence open-market operations in these assets can expand the economy by driving the currency and the long-term interest rate down.

Clearly there is something to this argument: perfect substitutability is a helpful modeling simplification, but the real world is more complicated. And in the absence of perfect substitution, these interventions will clearly have some effect. The question is how much effect – or, to put it a bit differently, how large would the BOJ’s purchases of dollars and/or JGBs have to be to make an important contribution to economic recovery. (You might say that it doesn’t matter – the BOJ can print as many yen as it likes. And perhaps that is the right thing to say in principle. But if supporting the economy requires that the BOJ acquire, say, 100 trillion yen in assets over the next four years – and if it is likely to lose money on those assets – the policy is going to be difficult to pursue).

A rigorous model of monetary policy in the face of imperfect substitution is difficult to construct (if only because one must derive that imperfection somehow). But a shortcut may be useful. Consider, then, the case of foreign exchange intervention – purchasing foreign bonds in an effort to bid down the currency. And let us look back at Figure 5, which illustrates how a liquidity trap can occur even in an open economy, because the desired capital export even at a zero interest rate will be less than the excess of domestic savings over investment.

What would the central bank be doing if it engages in exchange-market intervention in such a situation? The answer is that in effect it would be trying to do through its own operations the capital export that the private sector is unwilling to do. So a minimum estimate of the size of intervention needed per year is "enough to close the gap" – that is, the central bank would have to buy enough foreign exchange , i.e. export enough capital, to close the ex ante gap between S-I and NX at a zero interest rate. In practice, the intervention would have to be substantially larger than this, probably several times as large, because the intervention would induce private flows in the opposite direction. (An intervention that weakens the yen reinforces the incentive for private investors to bet on its future appreciation).

Here is some sample arithmetic: suppose that you believe that Japan currently has an output gap of 10 percent, which might be the result of an ex ante savings surplus of 4 or 5 percent of GDP. Then intervention in the foreign exchange market sufficient to close that gap would have to be several times as large as the savings surplus – i.e., it could involve the Bank of Japan acquiring foreign assets at the rate of 10, 15 or more percent of GDP, over an extended period. (Incidentally, does it matter if the interventions are unsterilized? Well, an unsterilized intervention is a sterilized intervention plus quantitative easing; the latter part makes no difference unless it affects expectations).

Purchases of long-term bonds would work similarly. In this case the central bank would in effect be competing with private investors as a source of investment finance (this would be true even if the intervention itself were in government bonds). Again, there would be an offset – with lower yields, private investors would divert some of their savings from bonds into short term assets or, what is equivalent under liquidity trap conditions, cash. So again the central bank would have to sustain purchases at a rate several times the ex ante savings-investment gap; in this case the BOJ might find itself purchasing long-term bonds at a rate of 10-15 or more percent of GDP.

There are obvious political economy problems with such actions. The prospect of having a quasi-governmental institution owning a trillion dollars of overseas assets, or most of the Japanese government’s debt, is a bit daunting. Of course this would not happen if a relatively brief period of unconventional monetary policy led to a self-sustaining recovery. But to believe in this prospect you must, as in the case of fiscal policy, believe that the economy is currently in a low-level equilibrium and can be jolted back to prosperity with temporary actions – a fairly exotic, though not necessarily wrong, view on which to base policy.

The same remarks applied to fiscal policy also apply here: while unconventional open-market operations are less certain a cure than their proponents seem to think, they could help, and might well be part of a realistic strategy.

Expectations: Finally, we return to the issue of inflation targeting. The basic point, once again, is that a credible commitment to expand the future money supply, perhaps via an inflation target, will be expansionary even in a liquidity trap. There are two problems, however, with this view. One is that it is not enough to get central bankers to change their spots; one must also convince the market that the spots have changed, that is, actually change expectations. The truth is that economic theory does not offer a clear answer to how to make this happen. One might well argue, however, that one way to help make a commitment to do something unusual credible is to do a lot of other unusual things, demonstrating unambiguously that the central bank does understand that it is living in a different world. Market participants are pretty much unanimous in their belief that unsterilized intervention would have a much bigger effect than sterilized, essentially because it would convey news about future BOJ policy; the same could be said of other actions, including quantitative easing. My personal view is that a country deep in a liquidity trap should try everything, even if careful analysis says that some of the actions should not matter; if, in the precise if annoying phrase I used in my first paper on the liquidity trap, a central bank must "credibly promise to be irresponsible", it should waste no opportunity to demonstrate its new spirit.

The other problem is that the policy shift must not only be credible but sufficiently large. A too-modest inflation target will turn into a self-defeating prophecy. Suppose that the central bank successfully convinces everyone that there will henceforth be 1 percent inflation – but that a real interest rate of minus 1 percent is not low enough to restore full employment. Then despite the expectational change, the economy will remain subject to deflationary pressure, and the policy will fail. Half a loaf, in other words, can be worse than none.

7. Concluding remarks

The whole subject of the liquidity trap has a sort of Alice-through-the-looking-glass quality. Virtues like saving, or a central bank known to be strongly committed to price stability, become vices; to get out of the trap a country must loosen its belt, persuade its citizens to forget about the future, and convince the private sector that the government and central bank aren’t as serious and austere as they seem.

The strangeness of the situation extends to policy discussion. Because the usual rules do not apply, conventional rules of thumb about policy become hard to justify. We usually imagine that policy is more or less based on conventional models – in particular, that normally policy will be based on the simple, rather dull models in the textbooks rather than exotic stories that might be true but probably aren’t. In the case of the liquidity trap, however, conventional textbook models imply unconventional policy conclusions – for inflation targeting is not an exotic idea but the natural implication of both IS-LM and modern intertemporal models applied to this unusual situation.To defend the conventional policy wisdom one must therefore appeal to various unorthodox models – supply curves that slope down, demand curves that slope up, multiple equilibria, etc.. So unworldly economists become defenders of analytical orthodoxy, while the dignified men in suits become devotees of exotic theories.

What I hope that I have done in this paper is to make clear how conventional the logic behind seemingly radical proposals like inflation targeting really is, and conversely how hard it is to rationalize what still passes for sensible policies among many officials. Let’s see it it works this time around.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Chart: The Collapse In Global Trade - Planet Money Blog : NPR

"The big elephant in the room." (Carl Weinberg/High Frequency Economics)

I've been waiting for a paper like this

Steve Kaplan and Joshua Rauh write:

"...the top 25 hedge fund managers combined appear to have earned more than all 500 S&P 500 CEOs combined (both realized and estimated)."

Here is the link, here is the non-gated version.

...there is no evidence of a change in social norms on Wall Street. What has changed is the amount of money managed and the concomitant amount of pay.

There is a great deal of analysis and information (though to me, not many surprises) in this important paper. The authors also find no link between higher pay and the relation of a sector to international trade.

America’s Chinese disease

...the Fed is engaged in massive “quantitative easing” — a misleading term, but I guess we’re stuck with it. What it basically means is that the Fed is selling Treasury bills or their equivalent (interest-paying excess bank reserves are essentially the same thing), while buying other assets, expanding its balance sheet enormously in the process.What kinds of other assets? Mortgage-backed securities; securities backed by credit-card debt; longer-term government debt; etc..

One type of asset the Fed has not been buying is foreign short-term securities. But that’s not because such purchases would be ineffective. On the contrary, selling domestic short-term debt and buying its foreign-currency counterpart is the essence of a sterilized foreign-exchange-market intervention, which is a time-honored way of gaining a competitive advantage and helping your economy expand.

And some countries have, in fact, made foreign-currency purchases a part of their quantitative easing strategy — Switzerland in particular. The only reason the Fed isn’t doing this is that we’re a big player, and can’t be seen to be pursuing a beggar-thy-neighbor strategy.

But now ask the question: what would the effect be if China decided to sell a chunk of its Treasury bill holdings and put them in other currencies? The answer is that China would, in effect, be engaging in quantitative easing on behalf of the Fed. The Chinese would be doing us a favor! (And doing the Europeans and Japanese a lot of harm.)

Conversely, by continuing to buy dollars, the Chinese are in effect undermining part of the Fed’s efforts — they’re conducting quantitative diseasing, I guess you could say, hence the title of this post.

The point is that right now the United States has nothing to fear from Chinese threats to diversify out of the dollar. On the contrary, if the Chinese do decide to start selling dollars, Tim Geithner and Ben Bernanke should send them a nice thank-you note.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Aid Fueled Latest Surge on Wall Street

1. Bankruptcy in which the banks do not fully pay back what they owe. The problem is that when big banks do this, the entire financial system would freeze up which was already starting to happen. This is why some banks are "too big to fail."

2. Give the banks money. This was Paulson's original plan. He wanted to buy the "toxic assets" for more than they were worth. None of the TARP money actually bought any toxic (or "troubled") assets even though the first two letters of the acronym stand for "troubled asset".

3. Loan the banks money at low interest rates and guarantee the bank debt. This was what the Paulson Plan did. The idea is for the banks to be able to keep making profitable loans at higher interest rates and thereby make enough profits to restore their capital.

4. Give the banks money by buying their stock. This was decried as socialism and/or nationalism because it would mean that the government would own a majority of some of the sickest banks, but all the other options except #1 were socialist too and this option has the advantage that the taxpayers could get their money back (when stock values are restored with the health of the banks) rather than the bank owners and managers getting much of the profits of the bailout as is now happening.

Because we went with option #3, the banks are now making big profits which was what the TARP plan hoped would happen. Unfortunately, the banks are not loaning much money to small businesses who are the main drivers of employment growth at the end of recessions. The big banks are finding it more profitable to use their low-interest government-subsidized money to make risky bets on the financial markets instead and why not? What do they have to lose?

NYTimes.com:

Many of the steps that policy makers took last year to stabilize the financial system — reducing interest rates to near zero, bolstering big banks with taxpayer money, guaranteeing billions of dollars of financial institutions’ debts — helped set the stage for this new era of Wall Street wealth.

Titans like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase are making fortunes in hot areas like trading stocks and bonds, rather than in the ho-hum business of lending people money. They also are profiting by taking risks that weaker rivals are unable or unwilling to shoulder — a benefit of less competition after the failure of some investment firms last year.

So even as big banks fight efforts in Congress to subject their industry to greater regulation — and to impose some restrictions on executive pay — Wall Street has Washington to thank in part for its latest bonanza.

...A year after the crisis struck, many of the industry’s behemoths — those institutions deemed too big to fail — are, in fact, getting bigger, not smaller. For many of them, it is business as usual. Over the last decade the financial sector was the fastest-growing part of the economy, with two-thirds of growth in gross domestic product attributable to incomes of workers in finance.

Now, the industry has new tools at its disposal, courtesy of the government.

With interest rates so low, banks can borrow money cheaply and put those funds to work in lucrative ways, whether using the money to make loans to companies at higher rates, or to speculate in the markets. Fixed-income trading — an area that includes bonds and currencies — has been particularly profitable.

“Robust trading results led the way,” said Howard Chen, a banking analyst at Credit Suisse, describing the latest profits.

...A big reason for Goldman Sachs’s blowout profits this year has been the willingness of its traders to take big risks — they have put more money on the line while other banks that suffered last year have reined in such moves. Executives say there are big strategic gaps opening up between banks on Wall Street that are taking on more risks, and those that are treading a safer path.

Banks that have waded back into the markets have been able to exploit large gaps in the prices of various investments, a feature of the postcrisis financial markets. The so-called bid-ask spreads — the difference between the price at which banks are willing to buy things like bonds, and the price at which they are willing to sell — are roughly twice what they were two years ago.

As Goldman Gloats, What Does It Matter For Us?

NPR: "Should we care about Goldman's profits and compensation? It's pretty gauche when your take-home pay is millions of dollars while some of your neighbors can't find work. But is it wrong? Is it something those of us on the outside should care about?

Normally, I'd say it's nobody's business. What people get paid is best left to the marketplace.

But Goldman Sachs is different because those of us on the outside are really on the inside. Goldman Sachs was propped up with our money. Not the money it took directly from the government and paid back. The money that AIG gave it that really came from the taxpayer.

Goldman Sachs being proud of its performance this year is like the Harlem Globetrotters bragging that they went undefeated. It's not really a normal competition.

Goldman Sachs played the same game as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers — they made lousy investments financed with borrowed money. When the assets fell in value, Bear and Lehman died. They were reckless with other people's money.

But Goldman Sachs is still here, Why?

Part of the reason is that maybe it took a little less risk and maybe hedged against that risk a little better. But part of the reason Goldman lives and thrives is that the government bailed out AIG. Almost 13 billion dollars of the money the government sent to AIG went out the door and over to Goldman Sachs. This money included loans and insurance Goldman bought on its bad bets. Some of that insurance turned out to be a bad bet, too. But Goldman didn't bear the cost. The taxpayers did."

Friday, October 16, 2009

When should the Fed raise rates? (even more wonkish) - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Greenspan Says U.S. Should Consider Breaking Up Large Banks

Oct. 15 (Bloomberg) -- U.S. regulators should consider breaking up large financial institutions considered “too big to fail,” former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said.I don't know how the government is supposed to break up the banks again. Greenspan probably could have prevented a lot of the mergers that created the superbanks, but now I think there is a more elegant way. When there is an externality, it can be corrected with a Pigouvian tax. The oversized banks impose an external cost on society and so they should be taxed at a higher rate than smaller banks. And if the tax is high enough, then the big banks will divide up of their own accord. If they have enough economies of scale, then they can stay big, but at least they will be paying back some of their dues to society.

Those banks have an implicit subsidy allowing them to borrow at lower cost because lenders believe the government will always step in to guarantee their obligations. That squeezes out competition and creates a danger to the financial system, Greenspan told the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

“If they’re too big to fail, they’re too big,” Greenspan said today. “In 1911 we broke up Standard Oil -- so what happened? The individual parts became more valuable than the whole. Maybe that’s what we need to do.”

Sunday, October 11, 2009

When should the Fed raise rates?

Friday, October 9, 2009

Econbrowser: Trade Procyclicality in the Current Recession: The View from the US

the current pace of trade activity as worse than that during the Great Depression.First, let's take a look at the exports-to-GDP and imports-to-GDP ratios.

Figure 1: Non-agricultural goods exports to GDP ratio (blue), and non-oil goods imports to GDP ratio (red). NBER recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, GDP 2009Q2 3rd release of 30 Sep 2009, NBER, and author's calculations.

Gold Standard Questions

What individuals or institutions are the biggest owners of the world's gold?

What would happen to the size of the world money supply if the entire world went back on the gold standard?

What are some economic problems with the gold standard?

What are some economic advantages of the gold standard?

Some libertarians like Alan Greenspan in the 1960s and Ron Paul today favor a return to the gold standard. What might be a political (rather than economic) reason libertarians tend to favor the gold standard more than others?

Capital Controls: Theory and Practice

Capital Controls: Theory and Practice:

"Among the economists promoting capital controls, Keynes was the most prominent. He was in favor of controls as a protective tool from the unstable international economy and the possibility of capital flight, which, among other things, causes a decrease in potential growth, erosion in the tax base, and redistribution from poorer to richer groups. From 1945-60 capital controls were unquestioned. During the immediate postwar period, freedom of capital movements was hardly an issue; international flows of capital through markets were unthinkable. The memories of the hectic 1920s and 1930s were still present and strict controls on international capital movements were needed for financial stability. According to Shafer (1995), developments at the end of the 1950's and early 1960's questioned the logic of the so-called Bretton Woods’ dichotomy, that is, controls for finance and freedom for trade. Capital account liberalization was taken seriously with the establishment of the OECD in 1961."

Warning: Capital Controls Are in Your Future

When Jim Rogers taught classes at Columbia, he liked to tell students that the US had a proud history of implementing capital controls, and warned them against going on the merry assumption that it would ever and always be easy to make cross-border investments. For instance, taxes on foreign securities transactins are a soft form of control and have been used to facilitate or restrict cross-border capital flows. The US lowered them when it abandoned Bretton Woods in 1971 to aid in adjustment of the price of the greenback.

Despite the hue and cry that we must keep trade and capital flows open, I have long believed that they would be restricted as financial reforms moved forward. The Carmen Reinhart-Kenneth Rogoff work shows convincingly that periods of high international capital mobility are associated with frequent banking crises. They do not assert that the relationship is causal, but I suspect it is. Capital that can move easily across borders is by nature difficult to regulate. It would require a considerable sacrifice of national sovereignity to devise rules and organizations that could do an adequate job of supervision. So a high level of international investment flows means lawless or seriously underregulated financial firms and activities. And we have just seen that this lawlessness eventually exacts unacceptably high costs to the real economy.

From the Financial Times:Governments still need the support of capital to ensure that the myth of prosperity dies slowly. If that support is not provided willingly, history shows that governments can conscript capital to the cause. So what sort of “national service” can we expect ?

A transaction tax on financial instruments is very likely… A suitably high transaction tax would force investors to hold shares for much longer periods and to engage management to control risk. This would reduce the need for governments to police risk-taking in corporations. What could be more laudable than a tax that turned everybody into Warren Buffett?

Capital controls are also more likely than investors believe….There is an inherent conflict between western governments’ need for finance to sustain living standards and capital’s need to seek out the greater growth opportunities in emerging markets. Whatever the long-term benefits in boosting returns on savings, the short-term political necessity of public financing is likely to necessitate slowing capital outflows.

Capital controls seem impossible to many, but when a choice has to be made between economic principle and government bankruptcy, they are a likely political response

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Wealthiest Americans Rebounding

Forbes details the 400 richest Americans. Venture Beat details the "struggles":Warren Buffett’s wealth took a dive this past year, losing $10 billion in value on his shares in Berkshire Hathaway. At least he’s not alone. More than three-quarters of Forbes’s annual list of the 400 richest Americans lost wealth in the past year.But it hasn't been all one direction. Since the stimulus / subsidized financing induced market bounce in March (a point in time which is detailed in March's report on wealthiest individuals on the planet), we see a bounce across the board.

Labor Force Shrinkage

how uncommon is a shrinking labor force? This is the first year over year decline since the early 1960's.

And why wouldn't individuals stop looking for a job. As the chart shows below, the number of people who have been unemployed longer than half a year has spiked to record levels.

And the long-term implications via Alan Greenspan."People who are out of work for very protracted periods of time lose their skills eventually. What makes an economy great is a combination of the capital assets of the economy and the people who run it. And if you erode the human skills that are involved there, there is a real and, in one sense, an irretrievable loss."Source: BLS

Still chasing shadows?

This article on the continued troubles in credit markets was informative. ...Here’s how I think about what has happened these past 2+ years. I think in terms of a sort of flow chart, showing ways that savers can connect with borrowers:

Traditionally — i.e., before the 1980s — the public put its money in banks, and banks made loans to borrowers: thus the diagonal arrow from banks to borrowers represents traditional banking.

By 2007, however, much of this traditional channel had been supplanted by shadow banking: debt was securitized, and the securities sold to the public — the straight arrow across the bottom of the figure.

Then the crisis came. The public rushed for safety, which basically meant guaranteed deposits. One rough indicator is holdings of MZM — money of zero maturity — which is the sum of bank deposits and money-market deposits:

In effect, the public rushed back into the banks. But the banks weren’t willing to lend out these excess funds. Instead, they accumulated deposits at the Fed:

To prevent a complete collapse of credit, the Fed in effect recycled these deposits back into private credit via the TALF and other securities-purchase programs. So funds now flow all around the first figure, getting to the public via “Bernanke banking” (my term.)

Everyone agrees that this is a stopgap, and we want to get the Fed out of the business of private lending over time.

Monday, October 5, 2009

Hangover theorists - Paul Krugman Blog - NYTimes.com

Also see Arnold Kling’s recalculation theory of business cycles.Somehow I missed this: via Steve Levitt, John Cochrane explaining that recessions are good for you:

“We should have a recession,” Cochrane said in November, speaking to students and investors in a conference room that looks out on Lake Michigan. “People who spend their lives pounding nails in Nevada need something else to do.”

So the hangover theory, which I wrote about a decade ago, is still out there.

The basic idea is that a recession, even a depression, is somehow a necessary thing, part of the process of “adapting the structure of production.” We have to get those people who were pounding nails in Nevada into other places and occupation, which is why unemployment has to be high in the housing bubble states for a while.The basic idea is that a recession, even a depression, is somehow a necessary thing, part of the process of “adapting the structure of production.” We have to get those people who were pounding nails in Nevada into other places and occupation, which is why unemployment has to be high in the housing bubble states for a while.

The trouble with this theory, as I pointed out way back when, is twofold:

1. It doesn’t explain why there isn’t mass unemployment when bubbles are growing as well as shrinking — why didn’t we need high unemployment elsewhere to get those people into the nail-pounding-in-Nevada business?

2. It doesn’t explain why recessions reduce unemployment across the board, not just in industries that were bloated by a bubble.

One striking fact, which I’ve already written about, is that the current slump is affecting some non-housing-bubble states as or more severely as the epicenters of the bubble. Here’s a convenient table from the BLS, ranking states by the rise in unemployment over the past year. Unemployment is up everywhere. And while the centers of the bubble, Florida and California, are high in the rankings, so are Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas.

So the liquidationists are still with us. According to Brad DeLong,

Milton Friedman would recall that at the Chicago where he went to graduate school such dangerous nonsense was not taught

But now, apparently, it is.

Update: Not to mention the idea that employment is dropping because workers don’t feel like working.

Why doesn't a housing boom — which requires shifting resources into housing — produce the same kind of unemployment as a housing bust that shifts resources out of housing.

Interesting FRED Graphs

DFEDTAR Federal Funds Target Rate (DISCONTINUED SERIES) DFEDTARL

DTB3 3-Month Treasury Bill: Secondary Market Rate

TWEXBMTH Trade Weighted Exchange Index: Broad

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Ezra Klein - A New Spin on the "Giant Pool of Money" Theory

The 'giant pool of money' hypothesis:

This is the idea that the actual trigger for the financial crisis was that emerging economies were running huge trade surpluses because a series of currency crises had convinced them that they couldn't sustain trade deficits. All that money, however, needed somewhere to go. And it went to developed countries. In particular, it went to America, and more specifically than that, to treasuries.

With Treasury bond yields falling through the floor, there was considerable demand for safe assets with better yields. The financial sector, sensing a market opportunity, jumped into the breach with securitized loans and AAA tranches and all the rest. Meanwhile, the strangely low interest rates fed a housing and credit bubble. In this telling, the key culprit behind the financial crisis was not the doings on Wall Street, but the giant hose of money the rest of the world pointed at us. If this is true, then fixing the financial system is like taking medicine to cure your symptoms. The disease still exists.

That, at least, is how I've understood the argument. But I just had a conversation with Steve Pearlstein that's making me somewhat reconsider the point. The causality, he argued, isn't as clear as all that. It may be that we developed these exotic financial instruments as a response to the river of money being pumped into our system. Or it may go the opposite way: That money was pumped into our system because we concocted abnormally attractive investments that caught the eye of foreign investors.

This is a slightly different spin on the same argument: In this telling, the current account deficit was still the problem. But it grew so large not because of foreign investors but because of Wall Street's decisions. Without the development of seemingly safe, high-return assets, that money would have been left to low-yield treasuries, and because those wouldn't have delivered sufficient returns, the money would have ended up going elsewhere. If that's true, then it may be that sufficient regulation of the financial sector actually could do quite a bit to ease our current account problems.

Friday, October 2, 2009

Much ado about multipliers

IT IS the biggest peacetime fiscal expansion in history. Across the globe countries have countered the recession by cutting taxes and by boosting government spending. The G20 group of economies, whose leaders meet this week in Pittsburgh, have introduced stimulus packages worth an average of 2% of GDP this year and 1.6% of GDP in 2010. Co-ordinated action on this scale might suggest a consensus about the effects of fiscal stimulus. But economists are in fact deeply divided about how well, or indeed whether, such stimulus works.

The debate hinges on the scale of the “fiscal multiplier”. This measure, first formalised in 1931 by Richard Kahn, a student of John Maynard Keynes, captures how effectively tax cuts or increases in government spending stimulate output. A multiplier of one means that a $1 billion increase in government spending will increase a country’s GDP by $1 billion.The size of the multiplier is bound to vary according to economic conditions. For an economy operating at full capacity, the fiscal multiplier should be zero. Since there are no spare resources, any increase in government demand would just replace spending elsewhere. But in a recession, when workers and factories lie idle, a fiscal boost can increase overall demand. And if the initial stimulus triggers a cascade of expenditure among consumers and businesses, the multiplier can be well above one.

The multiplier is also likely to vary according to the type of fiscal action. Government spending on building a bridge may have a bigger multiplier than a tax cut if consumers save a portion of their tax windfall. A tax cut targeted at poorer people may have a bigger impact on spending than one for the affluent, since poorer folk tend to spend a higher share of their income.

Crucially, the overall size of the fiscal multiplier also depends on how people react to higher government borrowing. If the government’s actions bolster confidence and revive animal spirits, the multiplier could rise as demand goes up and private investment is “crowded in”. But if interest rates climb in response to government borrowing then some private investment that would otherwise have occurred could get “crowded out”. And if consumers expect higher future taxes in order to finance new government borrowing, they could spend less today. All that would reduce the fiscal multiplier, potentially to below zero.

Different assumptions about the impact of higher government borrowing on interest rates and private spending explain wild variations in the estimates of multipliers from today’s stimulus spending. Economists in the Obama administration, who assume that the federal funds rate stays constant for a four-year period, expect a multiplier of 1.6 for government purchases and 1.0 for tax cuts from America’s fiscal stimulus. An alternative assessment by John Cogan, Tobias Cwik, John Taylor and Volker Wieland uses models in which interest rates and taxes rise more quickly in response to higher public borrowing. Their multipliers are much smaller. They think America’s stimulus will boost GDP by only one-sixth as much as the Obama team expects.

When forward-looking models disagree so dramatically, careful analysis of previous fiscal stimuli ought to help settle the debate. Unfortunately, it is extremely tricky to isolate the impact of changes in fiscal policy. One approach is to use microeconomic case studies to examine consumer behaviour in response to specific tax rebates and cuts. These studies, largely based on tax changes in America, find that permanent cuts have a bigger impact on consumer spending than temporary ones and that consumers who find it hard to borrow, such as those close to their credit-card limit, tend to spend more of their tax windfall. But case studies do not measure the overall impact of tax cuts or spending increases on output.

An alternative approach is to try to tease out the statistical impact of changes in government spending or tax cuts on GDP. The difficulty here is to isolate the effects of fiscal-stimulus measures from the rises in social-security spending and falls in tax revenues that naturally accompany recessions. This empirical approach has narrowed the range of estimates in some areas. It has also yielded interesting cross-country comparisons. Multipliers are bigger in closed economies than open ones (because less of the stimulus leaks abroad via imports). They have traditionally been bigger in rich countries than emerging ones (where investors tend to take fright more quickly, pushing interest rates up). But overall economists find as big a range of multipliers from empirical estimates as they do from theoretical models.

These times are different

To add to the confusion, the post-war experiences from which statistical analyses are drawn differ in vital respects from the current situation. Most of the evidence on multipliers for government spending is based on military outlays, but today’s stimulus packages are heavily focused on infrastructure. Interest rates in many rich countries are now close to zero, which may increase the potency of, as well as the need for, fiscal stimulus. Because of the financial crisis relatively more people face borrowing constraints, which would increase the effectiveness of a tax cut. At the same time, highly indebted consumers may now be keen to cut their borrowing, leading to a lower multiplier. And investors today have more reason to be worried about rich countries’ fiscal positions than those of emerging markets.

Add all this together and the truth is that economists are flying blind. They can make relative judgments with some confidence. Temporary tax cuts pack less punch than permanent ones, for instance. Fiscal multipliers will probably be lower in heavily indebted economies than in prudent ones. But policymakers looking for precise estimates are deluding themselves.

A list of relevant papers is available at Economist.com/multipliers

There's gold in them thar standards!

Someone rather more partial to Ron Paul's arguments in favor of the gold standard than I am asks me to write a post outlining my objections to it. All right, here goes.

Money is a mysterious thing. It is a store of value, it is a medium of exchange. It is, in a fiat currency economy, worth only what people think it is worth, and what they think it is worth can be oddly affected by what they think it may be worth in the future, resulting in self-fulfilling feedback loops (at least in the short term). Even in non-fiat currencies, such as the gold standard, the value of the underlying asset can be changed by rising (or shrinking) demand for money. Economists studying this fascinating topic tend to suffer from migraines as they suffer from all the mysterious--hell, nearly mystical--attributes of money.

However, over the last fifty years, economists have settled on some very broad areas of consensus. The first is, as famous libertarian monetary economist Milton Friedman wrote, "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon". When the supply of money outstrips the demand, prices rise. And this is by no means limited to fiat currencies; see the great Spanish inflation of the 16th & 17th centuries, thanks to the steady influx of gold from the New World. Or check out the price of basic commodities in mining towns during the Gold Rush, when all anyone had was gold.

The second is that a little bit of inflation is okay--possibly even beneficial, since it helps the economy to overcome the problem of sticky wages when the relative value of labour has fallen. But a lot of inflation is very, very bad. Exhibit A is Zimbabwe; Exhibits B-∞ are every other economy that has had inflation near or above the double-digit mark; the higher the inflation, the worse the economy did. The feeling that the currency will experience an unpredictable amount of inflation dampens the willingness of the citizens to save and invest, which is why so many third-world loans are denominated in dollars.

The third is that deflation is also bad, and at the lower percentage values, often even worse than inflation. This surprises/offends/meets with the frank disbelief of many "sound money" types, who think that, barring local shortage, in an ideal world everything ought to cost the same or less than it did when Grandpa was a boy. (These sorts of opinions are cemented further by the fact that Grandpa, who is often the source of them, is usually living on a fixed income, and therefore feels that he would make out better in a deflationary economy.) The problem is, deflation does rather devastating things to anyone who has debt, since they now have to repay what they borrowed in more expensive dollars. Deflation means that, thanks to the abovementioned sticky wages, the economy has to deal with demand shocks by lowering output. Deflation can result in what's known as a liquidity trap, a concept pioneered by liberal economist John Maynard Keynes and best elucidated by liberal economist Paul Krugman back before he left economics writing to focus on his hatred of George W. Bush. Deflation is what made the Great Depression so memorable. Deflation is so bad that almost everyone agrees that moderate inflation, in the range of 1-2%, is better than risking even a small amount of deflation.

Advocates of a gold standard dispute this. They argue that America experienced a long, slow deflation throughout most of the 19th century, without anyone getting hurt. What they neglect to mention is that people did get hurt, repeatedly, in the period's awful financial contractions. Though we don't have modern economic statistics for the period, it's pretty clear that recessions were longer and deeper than they are now.

This is not only due to the gold standard; the era's primitive financial system and its approach to financial regulation, which often ranged between lighthearted and foolhardy, also played substantial roles. But the gold standard also has to stand up and take a bow. There's a strong correlation, for example, between how long a country hewed to the gold standard, and how badly it suffered from the Great Depression.

The gold standard cannot do what a well-run fiat currency can do, which is tailor the money supply to the economy's demand for money. The supply of gold grows--or not--depending on how much of the stuff is mined. Demand also fluctuates for non-economic reasons; gold has uses besides being money, like industrial components and jewelry.

The lone advantage of a gold standard--and it is a real advantage--is that it prevents governments from inflating the currency. The problem is, this is only moderately true. The government, after all, can always modify its gold standard. Yes, you say, but it will pay a price in the markets, and this is true, but this is the same price it pays when it prints more fiat currency. Such practices do not go unnoticed for long.

As James Hamilton has pointed out, gold-backed currencies, like all money with a fixed exchange rate, are subject to speculative attacks whenever the government's financial position looks weak. Such speculative attacks often require punitive economic measures to fight off, which is one of the reasons that America suffered so nastily from the Great Depression--it raised interest rates in the middle of a recession in order to defend the credibility of its currency.

Also, since devaluations tend to produce sharp changes in the values of currencies, rather than smooth appreciations or declines, the economic dislocations are magnified. Imagine you're a company with a contract denominated in dollars. If the value of the dollar gradually declines, you lose a little, but not too much, since you periodically renew the contract, giving you time to adjust the amounts. If, on the other hand, the devaluation pressure builds up over a period of years, and then all at once the government has to devalue by 20%, you end up badly hurt. You might go out of business. Now multiply that all across the country, and you can see why recessions used to last for years.

In short, you don't get anything out of a gold standard that you didn't bring with you. If your government is a credible steward of the money supply, you don't need it; and if it isn't, it won't be able to stay on it long anyway. (See Argentina's dollar peg). Meanwhile, the limitations on the government's ability to respond to fiscal crises, the necessity of defending against speculative attacks in times of crises, and the possibility of independent changes in the relative price of gold, make your economy more unstable. It's a terrible idea, which is why there are so few economists willing to raise their voices in support of it.

Congresswoman Michele Bachmann. Proudly Serving the 6th District of Minnesota

Congresswoman Michele Bachmann. Proudly Serving the 6th District of Minnesota: "Washington, D.C., Mar 25 ...U.S. Representative Michele Bachmann (MN-6) has introduced a resolution that would bar the dollar from being replaced by any foreign currency.

“Yesterday, during a Financial Services Committee hearing, I asked Secretary Geithner if he would denounce efforts to move towards a global currency and he answered unequivocally that he would,' said Bachmann. 'And President Obama gave the nation the same assurances. But just a day later, Secretary Geithner has left the option on the table. I want to know which it is. The American people deserve to know.'"

Gold Bug Variations

The legend of King Midas has been generally misunderstood. Most people think the curse that turned everything the old miser touched into gold, leaving him unable to eat or drink, was a lesson in the perils of avarice. But Midas' true sin was his failure to understand monetary economics. What the gods were really telling him is that gold is just a metal. If it sometimes seems to be more, that is only because society has found it convenient to use gold as a medium of exchange--a bridge between other, truly desirable, objects. There are other possible mediums of exchange, and it is silly to imagine that this pretty, but only moderately useful, substance has some irreplaceable significance.

...

There is a case to be made for a return to the gold standard. It is not a very good case, and most sensible economists reject it, but the idea is not completely crazy. On the other hand, the ideas of our modern gold bugs are completely crazy. Their belief in gold is, it turns out, not pragmatic but mystical.

The current world monetary system assigns no special role to gold; indeed, the Federal Reserve is not obliged to tie the dollar to anything. It can print as much or as little money as it deems appropriate. There are powerful advantages to such an unconstrained system. Above all, the Fed is free to respond to actual or threatened recessions by pumping in money. To take only one example, that flexibility is the reason the stock market crash of 1987--which started out every bit as frightening as that of 1929--did not cause a slump in the real economy.

While a freely floating national money has advantages, however, it also has risks. For one thing, it can create uncertainties for international traders and investors. Over the past five years, the dollar has been worth as much as 120 yen and as little as 80. The costs of this volatility are hard to measure (partly because sophisticated financial markets allow businesses to hedge much of that risk), but they must be significant. Furthermore, a system that leaves monetary managers free to do good also leaves them free to be irresponsible--and, in some countries, they have been quick to take the opportunity. That is why countries with a history of runaway inflation, like Argentina, often come to the conclusion that monetary independence is a poisoned chalice. (Argentine law now requires that one peso be worth exactly one U.S. dollar, and that every peso in circulation be backed by a dollar in reserves.)

So, there is no obvious answer to the question of whether or not to tie a nation's currency to some external standard. By establishing a fixed rate of exchange between currencies--or even adopting a common currency--nations can eliminate the uncertainties of fluctuating exchange rates; and a country with a history of irresponsible policies may be able to gain credibility by association. (The Italian government wants to join a European Monetary Union largely because it hopes to refinance its massive debts at German interest rates.) On the other hand, what happens if two nations have joined their currencies, and one finds itself experiencing an inflationary boom while the other is in a deflationary recession? (This is exactly what happened to Europe in the early 1990s, when western Germany boomed while the rest of Europe slid into double-digit unemployment.) Then the monetary policy that is appropriate for one is exactly wrong for the other. These ambiguities explain why economists are divided over the wisdom of Europe's attempt to create a common currency. I personally think that it will lead, on average, to somewhat higher European unemployment rates; but many sensible economists disagree.

So where does gold enter the picture?

While some modern nations have chosen, with reasonable justification, to renounce their monetary autonomy in favor of some external standard, the standard they choose these days is always the currency of another, presumably more responsible, nation. Argentina seeks salvation from the dollar; Italy from the deutsche mark. But the men and women who run the Fed, and even those who run the German Bundesbank, are mere mortals, who may yet succumb to the temptations of the printing press. Why not ensure monetary virtue by trusting not in the wisdom of men but in an objective standard? Why not emulate our great-grandfathers and tie our currencies to gold?

Very few economists think this would be a good idea. The argument against it is one of pragmatism, not principle. First, a gold standard would have all the disadvantages of any system of rigidly fixed exchange rates--and even economists who are enthusiastic about a common European currency generally think that fixing the European currency to the dollar or yen would be going too far. Second, and crucially, gold is not a stable standard when measured in terms of other goods and services. On the contrary, it is a commodity whose price is constantly buffeted by shifts in supply and demand that have nothing to do with the needs of the world economy--by changes, for example, in dentistry.

The United States abandoned its policy of stabilizing gold prices back in 1971. Since then the price of gold has increased roughly tenfold, while consumer prices have increased about 250 percent. If we had tried to keep the price of gold from rising, this would have required a massive decline in the prices of practically everything else--deflation on a scale not seen since the Depression. This doesn't sound like a particularly good idea.

So why are Jack Kemp, the Wall Street Journal, and so on so fixated on gold? I did not fully understand their position until I read a recent letter to, of all places, the left-wing magazine Mother Jones from Jude Wanniski--one of the founders of supply-side economics and its reigning guru. (One of the many comic-opera touches in the late unlamented Dole campaign was the constant struggle between Jack Kemp, who tried incessantly to give Wanniski a key role, and the sensible economists who tried to keep him out.) Wanniski's main concern was to deny that the rich have gotten richer in recent decades; his letter is posted on the Mother Jones Web site, and makes interesting reading.

But, particularly noteworthy was the following passage:

First let us get our accounting unit squared away. To measure anything in the floating paper dollar will get us nowhere. We must convert all wealth into the measure employed by mankind for 6,000 years, i.e., ounces of gold. On this measure, the Dow Jones industrial average of 6,000 today is only 60 percent of the DJIA of 30 years ago, when it hit 1,000. Back then, gold was $35 per ounce. Today it is $380-plus. This is another way of saying that in the last 30 years, the people who owned America have lost 40 percent of their wealth held in the form of equity. ... If you owned no part of corporate America 30 years ago, because you were poor, you lost nothing. If you owned lots of it, you lost your shirt in the general inflation.

Never mind the question of whether the Dow Jones industrial average is the proper measure of how well the rich are doing. What is fascinating about this passage is that Wanniski regards gold as the appropriate measure of wealth, regardless of the quantity of other goods and services that it can buy. Since the dollar was de-linked from gold in 1971, the Dow has risen about 700 percent, while the prices of the goods we ordinarily associate with the pursuit of happiness--food, houses, clothes, cars, servants--have gone up only about 250 percent. In terms of the ability to buy almost anything except gold, the purchasing power of the rich has soared; but Wanniski insists that this is irrelevant, because gold, and only gold, is the true standard of value. Wanniski, in other words, has committed the sin of King Midas: He has forgotten that gold is only a metal, and that its value comes only from the truly useful goods for which it can be exchanged.

...